The blue plaque: if referring to the building itself, is out by about 15 years. If referring to the plot it is out by almost 60 years! Given that 30% of Glasgow tourism is driven by culture & heritage one would hope sense would prevail and the plaque corrected to reflect the true legacy.

Owners of Jacobean plot 1760 – 1836

1760 – Alexander Spiers of Elderslie. Merchant. 1 Mercantile ‘god’ of Glasgow.

1770 – George Oswald of Scotstoun. Merchant. 2 Later Rector of Glasgow University.

1793 – John Dunlop of Rosebank. Merchant. 3 Lord Provost of Glasgow 1794-96.

1794 – John Brown. Merchant. 4 ‘Master of Work’.

1800 – James Dennistoun 15th of Colgrain. Merchant. 5

1808 – Findlay, Duff & Co. 6 Extensive colonial merchants.

1826 – Matthew Brown of Crossflat. Industrialist. 7

1836 – Misses Brown (daughters of the deceased Matthew Brown)

…

1946 – 1996 ‘Browns’ Proprietors of ‘The Jacobean Corsetry’ business.

1996 – Present owner.

John Jospeh Burns of HolmesMiller Architects gave an excellent talk at the Old Glasgow Club recently concerning the history of the humble Glasgow tenement. This seemed an opportune moment to update the ongoing research on the Jacobean Corsetry.

During the recent 2022 conversion of the ground floor I had the chance to look past the normally closed large wooden storm shutter doors of the Jacobean Corsetry. Behind there were more steps into the Jacobean proper. The threshold transition with change in levels from exterior to interior felt clumsy and not what I’d have expected from a Georgian entrance.

In the Buildings of Scotland: Glasgow by Williamson, Riches & Higgs (1990) pg190 “The façade has paper thin Soanian details, though the tripartite door case is slightly more robust and old-fashioned”. Nowhere else in the literature does anyone hint that the ground floor may be a remnant of an earlier building. But equally the mish-mash of styles might hint that the work is ‘hybrid’ but more on that later.

When I compare this door case and fine ionic capital to surviving door cases around George Square, South Frederick and Cochrane Street & Virginia Street it doesn’t quite match in ‘feel & weight’ & quality of execution. When I compare to Charlotte Sq Edinburgh the ‘fit’ in terms similarity of scale & execution matches better.

Looking again outside, I was reminded of two features that niggled, that I couldn’t easily explain.

- The fine double ionic pilasters that frame the doorway. Why does the outside pair fall short?

- The ‘blank’ on the first floor centre window where one might expect some ornamentation or balustraded balcony. It’s not even incised in line with the exterior ornamentation leaving it looking rather incongruous even with such a plain façade.

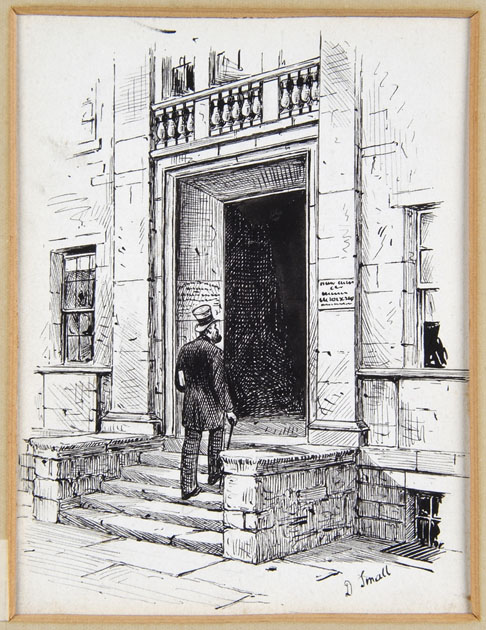

It was on discovering a print (circa 1870) by David Small of ‘an old Miller Street doorway’ that I was reminded that Glasgow Townhouses in the 18th century would project stairs out onto the pavement. His sketch of the entrance appears to show scalloped entrance at the top of a wide flight of straight stairs. On the 1st floor a tripartite, possibly venetian, window is enhanced with a balustraded balcony and framed by pilasters .

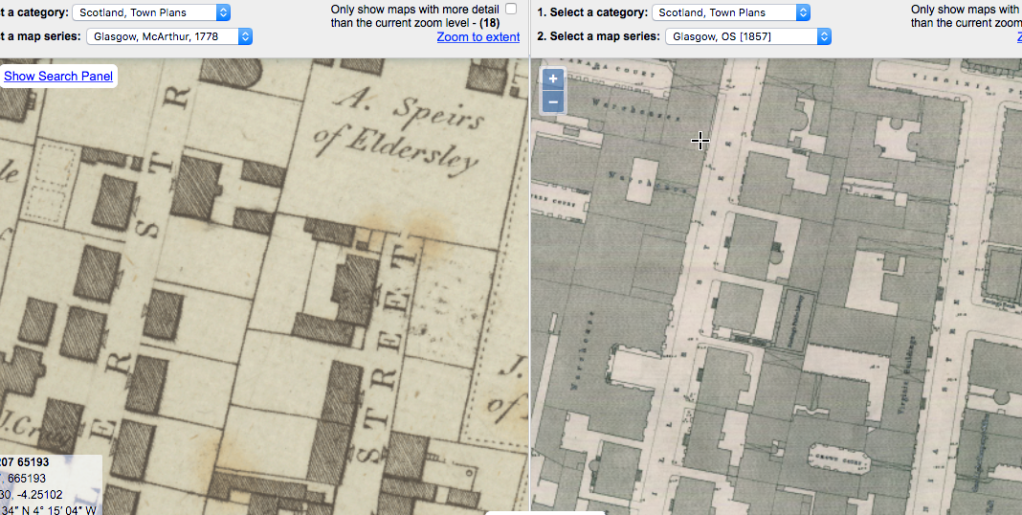

This caused me to revisit the maps that had served me well McArthur’s 1778 clearly reflects wide stairs. But Flemings map of 1807 dispenses with all stairs. However, the Glasgow OS map of 1857 gives the clearest and most accurate representation of all the stairs protruding in Miller & Virginia Streets at that time. The building with the most imposing stairway is The Jacobean Corsetry. This then explains the ionic pilasters falling short. As originally designed they would have met an exterior set of stairs descending to the street.

The entrance evidence combined with well documented style of Glasgow Townhouses of this period should inform us today that when looking at the Jacobean Corsetry we should recall how it was intended to be seen: as a grand residence.

The mansion garden that lay opposite would only have enhanced that impression. The garden’s removal circa1800 renounced its claim for ‘mansion’ status meaning that future generations would only come to see it as a commercial property.

The fact that the Jacobean Corsetry pilasters fall short but the Virginia Buildings to the south have no such shortcomings lend weight to the theory that the Jacobean was in situ first.and was not significantly altered at street level on transition from residential to commercial. This is supported by the fact that the only window line that matches between both buildings is the fourth floor. The top floor was added later to match the elevation of the Virginia Buildings to the south. This is evidenced by the quoin stones to the rear stopping short about the third floor & change in the treatment of the rubble work.

Both buildings as commercial propositions would have faced the same challenges if leveraging an earlier residential floor level. The Virginia Buildings accommodate this more successfully suggesting the architect had more scope with which to resolve this challenge. No such latitude appears to have existed for the Jacobean Corsetry to the north.

The blank panel below the first floor middle bays is open for interpretation. It might not have been intended to be seen. One can speculate that the grand stairs may have also supported a porch with pediment or similar adornment. Why else would the front stairs needed to have protruded to the extent that is suggested in the OS map of 1857? A porch with balcony would have served to obscure the view of the blank that we now see today.

The stone finish on the façade is of a high standard. Interestingly the only place where this is not the case is where the cornice of the entrance entablature returns onto the face. The stonework is ragged & unsightly. It is out of character. Was the original finish compromised when a porch was required to be taken down?

Equally, as is, the façade is suggestive of the Greek Revival period and fits with the well known assumption that build is in line with a 1816 purchase by Findlay, Duff & Co. This actually took place in 1808 not 1816 (Senex confused Bowman’s plot with Speirs and hence got the chronology mixed up). The sale was made by James Dennistoun of Colgrain.

Robert Smith’s adamitic tenement at 54-64Wilson Street as Arthur Bolton observed in 1922 (A T Bolton R and J Adam, vol.III, p.194) with its blind relieving arch and tripartite windows that are mirrored so well in that of the Jacobean Corsetry seems to infer some intent to create a cohesive street scape.

In council minutes it’s captured that in spring of 1791 Robert Smith jnr was petitioning the magistrates and city council to lay roads in Wilson & Brunswick Streets. This helpfully gives us a latest date for the completion of Robert Smith’s tenements.

Petition to magistrates and council by Robert Smith jnr wright in Glasgow that he had built sundry tenements in the new streets lately laid off within the city known by the names of Wilson St & Brunswick St., several houses of which are already possessed and those built are set to be inhabited by next whitsunday, on which account it becomes necessary to have them causewayed.

1 April 1791

The question is which came first, Jacobean Corsetry or 54-64 Wilson St? Let’s recap

1783 As per Lumsden’s map evidence of 1783 using John Miller’s Garden boundary as a datum suggests Speirs’ original mansion was still in situ.

1790 The Jacobean Corsetry was still in the private hands of George Oswald of Scotstoun. It would have held a prime axial position capping off the newly projected Wilson Street.

1790 Dugald Bannatyne one of the main partners of the Glasgow Building Company is resident in his new Ingram Street house capping off the northern end of Glassford street. His daughter Marion was born there 12 May 1791. This would later become the Star Inn circa 1798.

1791 Robert Smith confirms tenements in Wilson St & Brunswick Street built.

1793 Jacobean Corsetry sold to John Dunlop of Rosebank £3,000

c1794 Jacobean Corsetry sold to John Brown for a consideration of £2,000. A distress sale?

c1798 Dugald Bannatyne moves out of the city to his country house.

1798-1801 Feuing history for the remaining gardens of Bowman & Speirs shows that the western aspect of Wilson Street was narrowed and essentially closed off between 1798-1801.

1801 James Dennistoun of Colgrain residing Virginia Steet as per Tait Directory.

1803 James Dennistoun of Colgrain residing 23 Virginia Steet as per Tait Directory. (renumbered c1826 to 53 Virginia Street, the Jacobean Corsetry)

1807 Flemings map of 1807 reflects the modern day footprint of the Jacobean Corsetry.

1808 Disposition by James Dennistoun of Colgrain to Findlay, Duff & Co. of ‘new tenement with gateways’ Sasine concluded 1810.

1816 Robert Findlay transfers his residence at 42 Miller St. over to company of Richard Dennistoun and Findlay Duff & Co.

c1816 Virginia Buildings constructed.

We can surmise via status of owners that a building suitable to cap the main axial aspect of Wilson Street was already in situ by 1790 when Wilson Street was projected. The ownership provenance suggests as much.

The question is was the Jacobean Corsetry façade we know today already in situ before Dunlop sold or introduced later?

“kings from us, not we from kings,”

Dennistoun family motto

On reviewing the Sasine records and noting the name James Dennistoun that hadn’t flagged up previously I decided to explore the Tait Directory for Glasgow city to confirm. In 1801 & 1803 the residence of James Dennistoun of Colgrain is listed as 23 Virginia Street. This wasn’t what I was expecting. I assumed that the property had changed from residential to commercial on the 1794 sale by Dunlop to Brown. However, the change of use could only have happened later between 1808-1810 on the sale to Findlay Duff & Co.

This caused me to reassess. I now had a potential new build window for a residential property: 1794-1808. I recalled reading that Soane had designed a house 1798 for Robert Dennistoun(1756-1815) in Buchanan Street. Thirty plus copies of the drawings survive at Lincoln’s Inn Fields. All drawings are 3 bay except one dated January 1799.

Gavin Stamp writes that this 5 bay design was too wide for Robert’s Buchanan Street plot. (source: Gavin Stamp ‘Soane in Glasgow’, The Georgian Group Journal, Vol. xIII, 2003, pp. 181–200)

He also informs us that Soane also designed a house for Robert’s brother Richard in 1802. Richard also had an interest in Findlay, Duff & Co. This house was located at 31 Miller Street, east side north just south of Ingram Street. Miller Street runs parallel, west of Virginia Street.

This is where it gets intriguing. In 1802 Soane received payment of six guineas from Messrs Munn? and Brown for drawings made for ‘James Dennistoun Esq’. Stamp suggests this was probably James Robert ‘Ruffy’ Dennistoun, Robert’s son. But Robert didn’t marry until 1797 so on dates alone this rules out that hypothesis. On examining both the Golfhill & Colgrain Dennistoun lines the only suitable candidate is indeed James Dennistoun 15th of Colgrain.

The price of six guineas may not seem to be appropriate for a full redesign as per the documented costs of his father’s house. Assuming it is not part payment, does this suggest (i) it was simply for a façade ‘face lift’ and so the footprint we see today had already been extended by George Oswald of Scotstoun previously from Speirs’ original house? Or (ii) Given that the Dennistouns already had full detailed plans from the office of Soane for his brother’s house they were content to redeploy the tradesmen and execute by themselves. (iii) Given the houses main axial position could Soane have been content to oblige an existing customer if he thought more commissions would result. I shall defer to the experts of the excellent Soane Museum on this instead of idle speculation.

Mr. Connel bets against Mr. Finlay a bottle of rum that Mr. Jas. Dennistoun will rout as a cow louder and better than Mr. Henry Monteith.”

Board of Green Cloth 3rd March, 1812.

‘Adversa Virtute Repello’

Colgrain Motto: “I repel Adversity with Valor”

Looking at the feu history again of the Jacobean Corsetry we see Dunlop sold to John Brown in 1794. We have the Tait directory confirming a James Dennistoun of Colgrain lived at 23 Virginia Street 1801-1803. (This was later renumbered to 53 Virginia Street c1826) And finally we have that drawing of a 5 bay townhouse made in January of 1799 for Robert Dennistoun Esq. with an elevation looking surprisingly similar to the Jacobean Corsetry.

In terms of the architecture both sat on a half sunk basement; straight stair case leading to a door case flanked by double pilasters. A relatively plain entablature. The first floor centre bay, of five, of plain tripartite design. And most importantly we have Soane’s trademark incised ornamentation that was vilified in ‘the Modern Goth’, 1796.

‘… To see pilasters scored like loins of pork, To see the Order in confusion move, Scroles fixed below and Pedestals above, To see defiance hurled at Greece and Rome …’

Soane was no stranger to Glasgow patronage as evidenced by his work in both Buchanan Street & Miller Street for the Dennistoun brothers. But his only documented visit was in 1781 staying at the Black Bull Inn at the foot of Virginia Street.

Certainly the Jacobean Corsetry was increased in height later to match the elevation of its southern neighbour the Virginia Buildings of c1816. However, the use of incised detail on the Virginia Buildings as a unifying feature would imply this was already present on the Jacobean Corsetry.

Soane’s elevation responds sympathetically to the earlier adamitic buildings of 54-64 Wilson Street and would have enhanced the arcaded streetscape of that first west end around Wilson Street.

One can speculate if an old apprentice such as Robert Morison(c1748-1815) oversaw the build. (See 26,28, 30 Howe St., Edinburgh b1807 for what looks like similar architrave detail around centre bays)

Peter Nicholson(1765-1844) who worked in London for 11 years as a joiner, teaching and writing about practical architecture prior to returning to Glasgow in 1800 to work as an architect may have been familiar with Soane’s work.

David M Walker, writing in Stamp and McKinstry’s ‘Greek Thomson’ 1999 p25 ponders the development of David Hamilton(1768-1843) and how he could have “acquired a knowledge of Sir John Soane’s practice which extended far beyond what could have been gleaned from the short lived house that master designed in 1798 for Robert Dennistoun.”

If one looks at Hamilton’s Theatre Royal b1805 on Queen Street you see as has been noted by others a very Soanian roofline uncommon for Glasgow of the time. I see it on no other drawing of a public building in Glasgow prior to this date, (Hutcheson Hospital exc). It is divergent from the balustrades and pediments which were the order of the day.

Gavin Stamp in his excellent treaty on Robert Dennistoun’s house notes that Dennistoun would later be on the committee for the Theatre Royal in Queen St in 1803. Graeme Smith an authority on Glasgow theatres of this period ratifies this. (I thoroughly recommend his new book on the early built history of Blythswood. )

But what would have given a relatively new architect such as David Hamilton the confidence to introduce this on a public building? Did Dennistoun’s Virginia Street residence set the scene (pun) for the Theatre and inform this new direction for public architecture in Glasgow?

When Dennistoun was visiting London in March 1800 Stamp writes “he called on Soane twice…and on the second visit, after dining in Lincoln’s Inn Fields, they ‘went to the play’ together.”

This might not be the only documented relationship with Soane that owners can offer. The previous owner George Oswald was married to Margaret Smyth. Her mother was Mary Graham daughter of James Graham of Braco. A possible relation Colonel Thomas Graham 1st Baron Lynedoch commissioned work from Soane. More research is required. But the point I’m trying to make is the status & means of the owners of the plot would allow them the privilege to seek out ‘the best’. As evidenced by Lord Provost John Dunlop of Rosebank previously seeking out Robert Adam in 1792.

Whilst we cannot say for certain if 23 Virginia Street as it was known then or Dennistoun himself influenced any design decisions of David Hamilton for the Theatre Royal what we can say and be reasonably sure about is that Soane’s incised detail with little to no additional ornamentation did not really catch on in Glasgow. Executed on a main axial plot the light ornamentation faded from distance rendering the façade plain and unremarkable, especially when it was mutilated and extended upward to four stories.

In fact Glasgow’s rigid grid system with long straight streets only really gives an architect one plane on which to grab one’s attention. Most times as a viewer you have to be stood directly in front to appreciate the detail. As a pedestrian walking past, light incision alone is not going to make you ‘stop & look’.

Soane’s elevation for Virginia Street would be mutilated later, on the purchase by Findlay Duff & Co. possibly at the hands of Robert Scott (1770-1839) the architect of the Virginia Buildings to the south.

I now believe the Jacobean Corsetry essentially dates from c1799-1802 and is from the office of Sir John Soane.

Postscript I: Why was provenance lost?

Primarily as a result of J.B. & Senex mixing up Bowman’s & Speirs’ plots and thus the chronology. However, other factors were at play too.

If the build date is true c1799-1802 and on the assumption that Findlay, Duff & Co. extended upward then that dates the lifespan of the original elevation to 1810-1822, some 10-20 years. An even shorter period than Robert Dennistoun’s house on Buchanan Street.

The Council Minutes support the premiss that south of Ingram Street to Wilson street building work is well established by late 1790. Looking at the sale history of Bannatyne & Dunlop homes we can deduce that the ‘smart’ money was already moving out by 1798 to quite literally greener pastures with the less well heeled following closely behind to the more salubrious Blythswood developments of William Harley et al which started in earnest circa1800. James Dennsitoun of Colgrain had moved from his new home by c1808.

This calibrates the timeline of Glasgow’s first ‘west end’ around Wilson Street as would have been originally envisaged by its patrons to essentially little more than a decade. Hardly anytime in the life of a city for cultural memories to be laid down for the next generation. More like a blink of the eye, an interlude, to be quickly forgotten.

In Bannatyne’s own memoirs less than half a page is devoted to the entire enterprise. Think about that. It may help explain why so little contemporary records exist. These individuals were too busy with ‘higher’ ideals, becoming enlightened to give much importance to the simple act of house building. Equally they had moved on to ‘0.2’ the next big and better thing, namely Blythswood.

With no time for a cultural memory to take hold, as David Lamont offers in his book ‘Georgian Glasgow’, this may partly explain why so little knowledge has been passed down about this early building phase.

Postscript II: A lucky find

I’d seen reference to 53 Virginia Street being a girls’ school at one point. As a consequence of this research I’ve established the boarding school was in fact across the street located in rooms of the surviving warehouse of Henry Hardie & Co. from c1799 and was run by Robert Burn’s ‘Mauchline Belle’ Jean Smith for nearly 30 years. This building is still in situ at 52 Virginia Street and must be one of the oldest educational establishments surviving in the city outside of the Cathedral and University. But in another twist with establishing the connection with Dennistoun I find the Jacobean was indeed a girls’ school for a very brief period. It seems ironic that in this ‘no mean city’ two of Glasgow’s oldest educational buildings still extant were dedicated to female education.

Biography Notes:

1 Alexander Speirs: Married into the Cary (Carey) family, plantation owners in Virginia. His wife Sarah Cary the youngest daughter of Henry Cary jnr. of Ampthill in Chesterfield County. Henry Cary’s main occupation was as a contract builder. His buildings include the President’s House, Williamsburg Virginia. Every President of the United States from Woodrow Wilson to Dwight D. Eisenhower has visited the President’s House, as did Winston Churchill. Queen Elizabeth II was a guest at the President’s House twice: in 1957 and May 2007, as part of celebrations for the 350th and 400th anniversaries respectively of the establishment of the Jamestown Colony. When Henry died c.1749 he left to his son-in-law Alexander Speirs, three thousand acres of land on Willis Creek, “currently in his possession” also the plantation slaves, cattle, horses etc., “including a negro wench named Sarah and a negro girl named Nell”. The American proceeds would have helped fund in part his return to Scotland shortly after. (By 1885 his descendants at Houston House had around 10 indoor and 14 outdoor staff.)

(Speaking of ‘Houston’ , the ‘prestigious’ house of Alexander Houston & Co. was brought down by egregious speculation in enslaved people. Stephen Mullen writing in his excellent website ‘It wusnae us’ that Hugh Thomas as recently as 1997 describes it as ‘the worst financial disaster in the history of the British slave trade’. I am sure the enslaved people would be comforted to know the disaster was merely financial. Apparently, ‘too big to fail’ when it showed signs of collapse in the 1790s the government was forced to step in to mitigate the impact to the Scottish economy. Did this experience inform the UK approach to eventual abolition?

One other aspect that doesn’t receive enough attention is the merchant approach to bequests and the time value of money. Merchants wouldn’t simply, for example, bequest £100. They would bequest £80 with stipulation that the donation should only ‘vest’ when compound interest raised the amount to £100. In the same way would the government simply outlay the equivalent of £1bn compensation to plantation owners? Or would it write off £800m in the books with a view that once it accrued to £1bn then the compensation process could begin. Cold. Heartless. Business as usual. In an uncertain geopolitical time the government could not afford to leave itself financially exposed to the flagrant avarice of the merchants in the face of external threats across the water. As Houston & Co. demonstrated merchants would not have thought twice to fleece the government if there was a guinea to be made.

The UK was not operating in a vacuum. The competitive advantage that cheap enslaved labour afforded UK also assisted political foes in France and rest of the world. Giving a financial advantage to your competitor would have been perilous never mind political suicide. Geopolitical influence needed time to keep the playing field ‘level’.

Every right minded individual today recognises that, ideally, slavery should have been ended immediately. Compensation should have been given to the enslaved rather than the enslaver. Ironically that route might have proved a cheaper option for the Government purse. The law, conveniently as it was, prohibited that course. In reality, achieving abolition was far more complex no matter how difficult that is to stomach. Expectation of an immediate end was unrealistic, but merchants had already demonstrated a manageable time frame, of 12-24 months, as seen with the time they took to pivot from tobacco to cotton. The precedent had been set by themselves. One that the government was unable and/or unwilling to acknowledge let alone enforce. The current conversation around Dundas and the eventual time taken to bring about abolition is a valid one. Did the time value of money trump public sentiment to end the egregious practice? )

2 George Oswald: Nephew of Richard Oswald of the Paris Treaty and Bunce Island infamy. The ‘trading fort’, where abducted Africans were sold, tortured and trafficked under inhumane conditions in their tens of thousands. Head of the major tobacco firm of Oswald, Dennistoun, & Co. He was also a partner in The Old Ship Bank and The South Sugar House. He and his wife would travel to Bath to have Gainsborough capture their portrait.

3 The name John Dunlop of Rosebank should resonate with any Robert Adam scholar. He was his last known patron. However, circumstances would transpire against both. Adam died in March of 1792, laying to rest any ambitions John Dunlop had to engage his services and emulate his father’s house, primus, on Argyle Street. He himself, aka the ‘killing provost'(an unfair moniker), would become ‘unfortunate’, necessitating a distress sale of the Jacobean Corsetry in 1794 for £2,000, losing a third of his investment in one year. The triple whammy of the French Revolution, war on the continent and a Yellow Fever epidemic in the US had served to out-flank and constrain free movement and supply of goods and services creating a liquidity crunch for some houses who had over extended. His brother James’s well publicised troubles at Colin Dunlop & Co. may have contributed in bringing down the house of John Dunlop. However, familial patronage would enable him to land a prime Collector of Customs position in Bo’ness c.1794. He was the author of the beautiful songs “Here’s to the year that’s awa,” and ” O dinna ask me gin I lo’e ye,” and other poems. He had his portrait made by Sir Henry Raeburn, R.A.

4 John Brown was the son of Captain Alexander Brown of an Ayrshire family, who apparently held a commission in the Royal Navy from Queen Anne. John Brown himself was a ship master in Port Glasgow and was Dean of Guild in 1746-7 and Lord Provost of Glasgow in 1752-54. He was made a magistrate in 1779, and appointed Dean of Guild again 1784-5. He was married, 13 Sept 1735 to Jean Dennistoun sister of James Dennistoun 14th of Colgrain, George Oswald’s business partner.

5 James Dennistoun: His son James Dennistoun of Colgrain 16th would marry George Oswald’s granddaughter Mary Ramsay in 1801. His brother Robert Dennistoun (1756-1815) was a partner in G&R Dennistoun & Co. and was one of the prime movers behind the formation of the Glasgow West India Association in 1807. The association was set up “for the protection of their various rights, privileges and interests”; indeed, they paid £50 to have an agent lobby in the London Society of West India Planters and Merchants. Iain Whyte has argued that contemporaries viewed Glasgow’s Association with its wealthy, politically active, and influential merchants as the most powerful body outside of London. Abolition was clearly detrimental to their business interests.

Robert Dennistoun and Alexander Campbell of Hallyards would enter business together as partners in the Newark Sugar Refining Company along with Alexander’s brother James Campbell of Newton Lodge. Their counting house was located between both clans living side by side in Buchanan Street south of Mitchell Lane. Robert died in 1815 survived by his widow, his brother-in-law Colin and others as trustees; compensation of £12,545 14s 9d was awarded in 1836 for the freeing of 253 slaves on three plantations he or his company owned in Trinidad. Stephen Mullen, writes, Chapter 6 The Great Glasgow West India House of John Campbell, senior, & Co. Recovering Scotlands Slavery Past ‘In his landmark study The Price of Emancipation, Nicholas Draper underlined the exceptional standing of the great merchant house of John Campbell, senior, & Co. On the abolition of plantation slavery in 1834, partners in the firm received over £73,000 compensation, which ranked the merchant house as the eighth-largest ‘mercantile beneficiary’ in Great Britain and the highest in Scotland.

6 It is easy to forget that when you look at the mature ‘Virginia Buildings’ complex that would eventually span from 42 Miller Street through to 53 Virginia Street you have forty(40) bays of real estate. An extensive warren of writers, agents, brokers, shippers and owners. All working in harmony for the extensive colonial operation of Findlay Duff and Co. This combined office complex must have been one of the largest in Glasgow if not Scotland outside of an industrial setting. To put this into context the stately Tontine Exchange and Coffee Rooms built for the City by Allan Dreghorn, from 1737, on the Trongate were 10 bays wide plus back court. Clark & Bell’s later Merchant’s Hall of 1843, Hutcheson Street, only nine bays.

7 Matthew Brown: He had extensive business interests. Primarily a brewer in Paisley(1783) he was also part of the management Committee in the business concern building the Glasgow, Paisley to Ardrossan Canal & subsequent Railway. Owner of New Mill Johnstone, Matthew Brown & Co. Cotton Spinners. Other business interests included the Portnauld Distillery at Inchinnan, Directorship of the Coffee House at the Cross Paisley, his interests also included a subscription to the House of Recovery and various involvements in the Port Glasgow area where he was a Justice of the Peace and Mayor of Paisley.

He built Crossflat House circa 1800. He died in 1836 when his son Andrew inherited his business and some of his property interests, these included the Estates of Auchentorlie, Paisley, and Whiteford. Andrew lived at his Broadstone Estate near Port Glasgow, and Crossflat was occupied by Matthew Brown’s three daughters until the death of their Brother Andrew in 1856 when they moved to Port Glasgow, putting the Crossflat Estate on the Market. It is interesting that Matthew Brown bequeathed the Virginia Buidings complex to his three daughters. They appear in the public valuation register from 1855.

© Cicerone: MerchantCityGlasgow. All Rights Reserved. 2023