Source: Getty.com

Until the eighteenth century there was no public meeting place in the city meaning the Town Council had held its deliberations in the Tolbooth. There had been several iterations that we are aware of:

- 1st Tolbooth c1400

- 2nd Tolbooth c1560

- 3rd Tolbooth 1626 seen above Fig.2 , of which only the steeple remains. It served as prison, Town Clerks Office and meeting-place of the Town Council for over a century.

By the early 1700s the Town Council was in need of more spacious accommodation. Accordingly the foundation stone of the first Glasgow Town Hall was laid by Provost Coulter in 1736 on the site adjoining the Tolbooth. The image below would appear to be pre 1736. If accurate it shows the dutch gabled building that was removed to make way for the first Town Hall. Note the loggia already in situ, around the cross dating from c1652, emulating Inigo Jones Covent Garden of 1630. (A photograph c1890s showing construction of Glasgow Cross Station confirm the dutch gabled building on the High Street which seem to infer a certain level of accuracy for the engraving.)

Source: Engraving Illustration for The Scots Worthies (Blackie, 1879)

The description concerning the build of the Town Hall from Renwick is problematic for me. He talks of six arches, with four added later in 1781. That would suggest irregular plot widths OR 3 or equal size of approx 33ft

Scots rod, 6 ells, or 5.648m 2x = 11.3m or 37ft.

From an architecture perspective given the design of the window pediments alternating segmented & triangular, then, in order to maintain balance you must have an odd number of bays/arches. I do not think Allan Dreghorn(1706-1764) would have designed something unbalanced from the outset with six bays. He would have started with five, However, as soon as they decide to expand they are constrained to ten bays which results in the finished unbalanced design as seen in Fig.1. I do not think William Hamilton would have introduced this irregularity if given the choice or ability to correct.

About the extension to ten bays:

“By March, 1781, the committee were busy over the plans of their buildings and alterations. The first architect employed was Mr. James Craig, but he was soon discarded for “a Mr. Hamilton, an Architect from London.” After some delay the plans were adjusted, but it was not till the beginning of 1782 that the work on the main building was set agoing. John Adam, a well-known builder, whose name survives in Adam’s Court, Argyle Street, was the mason, and a stiff-necked mason he was, for there were repeated appeals to the arbiter in his contract to say what should be done. William Craig was the wright.”

It would appear that the Tontine Committee might have felt some responsibility toward architect James Craig as they hire him c1786 (in consolation?) to complete their operations:

“In August, 1786, they advertised for tenders for its (sugar rooms) erection, but the contract was not made till July, 1789, when John Brown and Matthew Clelland contracted to finish the whole building for ,£1,814. The architect was James Craig.”

Matthew Cleland (mason) and John Brown (master of works). Little is known of Matthew Cleland, uncle of Glasgow’s greatest clerk of works James Cleland(1770-1840) accept that he married the daughter of one of Glasgow’s greatest known masons of the period, Mungo Naismith(1730-1770). John Brown would later be instrumental in delivering Robert Adam’s vision for the Trades Hall b1794 as it was he in capacity as builder delivered Adam’s design. He must have been very successful in his practice as we find him residing in Virginia Street between 1794-1800 in the prior townhouse of Alexander Spiers which he had purchased from Glasgow’s Lord Provost John Dunlop of Rosebank for £2,000 in 1794. On his death his trustees would sell to James Dennistoun of Colgrain who like his brothers it is thought employed Sir John Soane to design his city townhouse at number 23 Virginia Street, still extant (no.53), much mutilated, but still as Gomme & Walker state ‘owing something to the influence of Soane’.

As for the number of bays built being initially, six or five, the Scottish Architecture Dictionary notes similarities to Webb’s Gallery at Somerset House of 1662 (with its regal links to James VI of Scotland). That was only five bays for the reasons already outlined.

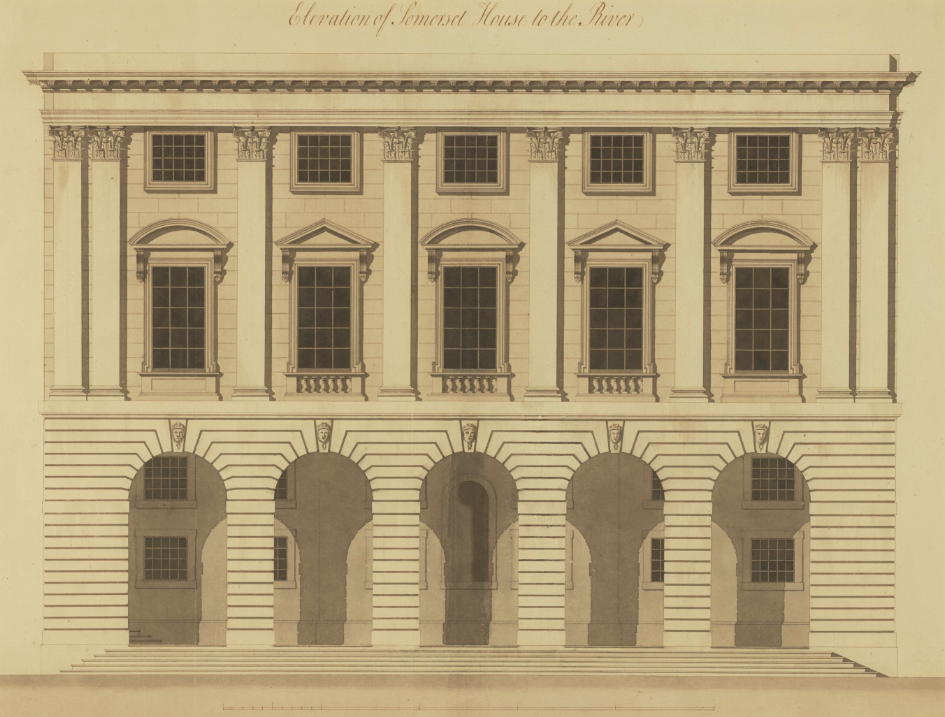

Somerset House b1662 by architect John Webb(1611-1672) throws up more questions than answers. Below, Fig.5 is a plate from Colen Cambell’s (1676-1729) Vitruvius Britannicus vI, plate 16, 1715. Note that its five bays, outer bays with triangular consoled architrave & balustraded windows on all five of the first floor windows.

Above Fig.6, is a pen and ink wash by William Chambers c1775 of Webb’s old Somerset House prior to his remodel. It would appear that Allan Dreghorn’s Tontine if it took its inspiration from Somerset House then it wasn’t from Vitruvius Britannicus but from life. The confusion is cleared up by RIBA which holds in their archive the drawing below which was supplied to Colen Campbell in 1710. It would appear he has been given an interim design and not the final version that was signed off for Somerset.

Source: © RIBA

Source: RCIN 914698

The painting by Sandby shows old Somerset House ‘in the flesh’ c1772 just prior to being demolished after years of deterioration. By this point the House had become home of the Royal Academy (of Arts) and as such a view that would have previously been out of reach for the vast majority became more accessible to a chosen few. The building fronted the Thames but given it was set back behind high walls it would have not been a view seen by many except from a distance. In 1736 that would have included Dreghorn. More likely its merely coincidental that parallels can be drawn. Lets not forget Glasgow already had loggia in situ from c1652 and wouldn’t have needed to emulate per se. Glasgow was merely retaining in its design what it had already become accustomed. Although style cues would have been sought to project status for the new build.

Source: With courtesy from Royal Collection Trust / © HM Queen Elizabeth II 2012

Source: (WORK 30/269)

Another building in London of this time was similar in style. It was street-side and accessible (to view) by all. In terms of influencing perceptions it held a greater capacity simply in terms of its visibility.

The taverns and coffee houses, like Lloyd’s Coffee House were a favourite haunt of merchants and sailors for up to date shipping news amongst other things. It was essential for trade & important to brokers for pricing insurance of both ship & cargo. Lloyd’s was situated near East India House fl1729-86 designed by architect Theodore Jacobsen. This building would have been known to Glasgow’s merchants of the plain stains. Indeed the East India Company would later have an ‘East India Association Office’ located in Virginia Buildings on Virginia Street. It would have been relatively new having been built in 1729 when in 1736 Dreghorn was possibly looking south for inspiration as he had done previously with St Martin’s in the Field. The statue of King William of Orange that stood outside the Tontine was gifted to the city by a Scottish East India Merchant by the name of James Macrae(1677-1744). His estate in Ayrshire called ‘Orange Field’.

Source: © British Library, P2189

East India House, Leadenhall Street was the London headquarters of the East India Company, from which much of British India was occupied until the British government took control of the company’s possessions in 1858. It is no surprise that this design would resonate as projecting power with the mercantile and trading class. (Macrae had been govenor of Madras for five years.) The architectural cues of the Tontine, sourced primarily via London would have been well known to Glasgow’s mercantile & landed class. Used to project sagacity, power & confidence. One suspects they also desired some of London’s mercantile success.

And with this success came the need, in 1781, to expand the old Town Hall with the William Hamilton commission. The expansion of the Tontine from five bays to ten, limited by plot width, has resulted in the imbalance of the segmented arches we see in the finished exterior. Internally we have very few descriptions, although, its grandeur was captured By Alexander Hay in his Modern Builders Guide.1

Source: The Modern Builders Guide by Alexander Hay, pub. Glasgow c1841.

Source: Reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland.

Constrained on three sides, the success of the remodel is all the more remarkable given how well the new building was received, a showpiece for the city. The last thing regarding Hamilton’s work here that’s not often considered was the combined scale of the Assembly Room, Coffee House and Exchange. Its footprint was impressive. Industrial complexes like the local Phoenix Foundry aside, only ecclesiastical buildings like the Cathedral and St Andrews Church, or scholastic like the University, or the new Royal Infirmary can compete. David Hamilton’s later Royal Theatre on Queen Street thought to be the largest provincial theatre of its time in Europe stands out too. To be confident enough to take on such a massive undertaking in a new city takes skill, experience, and self confidence. William Hamilton would appear to have had all three.

A relatively unknown image of the Trongate only recently re-discovered, (sold 2015 for a record price for the artist) showing the Tontine Hotel behind Macrae’s statue that he gifted to the city.

In September of 1911 a fire broke out causing damage of £60,000. Four firemen were badly injured in the blaze whilst trying to contain the spread and protect the historic building and surroundings. After 125 years at the Cross it was sadly replaced in 1912 by the building we see today.

- With thanks to George Fairfull-Smith; ‘Wealth of a City’ 2010. ↩︎

© Cicerone: MerchantCityGlasgow. All Rights Reserved 2023