Haldane Academy Trustee, The inclusion of Robert Scott, architect, in the management committee of the Haldane Academy Trust in 1833 would appear fitting. It signals an element of continuity with respect to the teaching of architecture in Glasgow as the head of city’s first dedicated architecture school.

The names of fellow architects on the committee like Hamilton & Herbertson slip off the tongue when discussing Glasgow architects of this period. The name Robert Scott does not, you’d be hard pushed to find anyone that could identify any of his remaining work. Neither flamboyant nor innovative, Gildard referred to him as “a ripe architect who thoroughly knew what he had to do,” but curiously couldn’t pinpoint his work apart from the now demolished St Mary’s Episcopal Church, Renfield Street. He would appear to have been grounded in the classical traditions but wasn’t afraid to venture (it is said successfully ) into early Gothic.

Not simply a teacher of architecture, he had a successful practice too. The clients we know about were of high social status:

- Robert Findlay of Easterhill

- The Dennistouns of Colgrain

- The City of Glasgow

- Dumbarton Council

- The Trades’ House

- The Merchants’ House

- The Andersonian Institution

- The Episcopalian Church

- The Bairds of Gartsherrie

- Admiral John Rouett Smollett of Bonhill

- John Buchanan of Ardoch (and Shipbank)

- North British Railway

Background

Robert Scott’s year of birth is uncertain. An Old Parish Record for the Gorbals dated 20 April 1839 capture his death due to ‘decline’ at the the age of 69. This would suggest a dob of c1770. Contemporary references that make mention of him suggest c1785. Dying intestate, his nieces and nephews with their respective spouses make a claim on his estate. Working backwards from their marriage dates suggests there may be validity to the d.o.b. suggested in the Gorbal’s Old Parish Record. If proven correct it might explain how Scott was able to receive such a thorough classical training as alluded to by Gildard.

It has recently been discovered that one of Robert Adam’s senior draughtsmen operated in the city for almost a decade c1780-90. Indeed some well known buildings had been attributed to the name without fully appreciating who that name was. We are told the city was beholden to this architect, as it was:

”so much indebted for its elegance. If indeed it challenges the admiration of strangers, we may thank him for he, during a residence of ten years, first inspired us with a taste for design, and taught us to relish the various beauties of Architecture.”

It might help explain how Scott was able to command such a distinguished clientele, and at the same time be entrusted to operate a private architecture school for almost thirty years without obvious public support or being a name that we would recognise today. Could Scott have received instruction from this individual who was held in such high esteem? If born c1770 the dates would appear to fit such a hypothesis.

John Scott, author of ‘Glasgow Delineated’, published 1821 (& 1826), may have been a relation given the keen architectural detail captured in his book and the interest shown in the city’s urban planning. He has this to say about the ‘capital of the west’ (pg.3):

“To a stranger who has seen the new town of Edinburgh, that of Glasgow may appear in some respects to disadvantage. There are few of those splendid and regular masses of building which everywhere abound in the metropolis. The streets, from too great economy of space are comparatively narrow, and many of them built with little or no regard to uniformity. It must be admitted, however, that a minute and studied regularity rather palls upon the sight, and that this circumstance has imparted to some of the finest streets in Edinburgh a degree of tameness and monotony, which is never felt in the capital of the west. It will be allowed also that Edinburgh owes much of its magnificence to its sublime and romantic situation, and to the singular effect of contrast which is produced by the abrupt and rugged separation between the old city and the new. Glasgow, on the other hand, is built in a form more compact and convenient. The arrangement of the streets is so simple, that a stranger becomes immediately familiar with it. The modem districts of the city are so naturally blended with the ancient that they seem to form one unique and original design. In this respect Glasgow has a manifest advantage over the metropolis; though for the same reason it falls short of it in bold and picturesque grandeur”… “The great boast of Glasgow, however, is the ingenuity of her artisans, her scientific institutions, and her operative and mechanical establishments.”

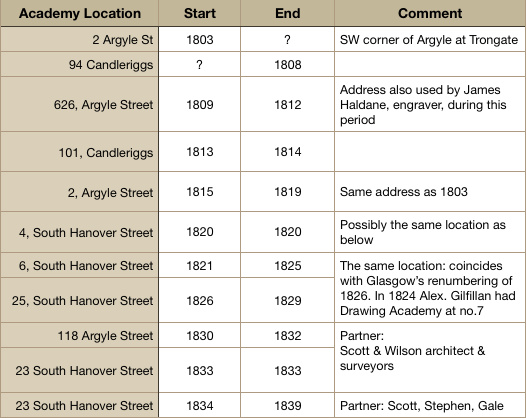

1803 is the earliest date captured of Glasgow’s first known commercial architecture academy at 2 Argyle Street. Robert Scott operated from various locations before settling in South Hanover Street until 1830. Almost 30 years of teaching; ‘Firmitas, Utilitas, Venustas’. He wasn’t quite finished with architecture though and would remain in practice until 1839.

(According to Colvin, the Academy was situated in George Street and he ran it in conjunction with James Watt. There may be credence to this partnership given the fact that when J&A Watt open up their Architecture Academy at no.9 Argyle Street in 1814, a year later Robert Scott appears back at no.2 Argyle Street where he’d begun his Academy c1803. Both Academies existing side by side for the next 3 years.)

Reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland.

The Virginia Buildings, Glasgow

Recent research enables Robert Scott’s first known independent work in Glasgow to be re-calibrated to c1816, namely the Virginia Buildings 37-49 Virginia Street built for the merchant Robert Findlay of Easterhill, a partner in the extensive colonial operation of Findlay, Duff & Co.

An old text stated that a ‘Robert Scott’ was responsible for building extensively in Virginia Street. However, with no specific buildings named or in what capacity eg developer/builder/mason/architect there was little to go on. Indeed, the Thistle Bank that lay opposite had as one of its partners Robert Scot, merchant.

A documents of 1822 relating to the lease of the Virginia Buildings for Findlay, Connal & Co. the later name for Findlay, Duff & Co. confirms the architect as ‘Robt. Scott’. I believe it is Robert Scott (c1770-1839) of the Architecture Academy mentioned earlier. There is no other record of an architect of this name working in the city.

Fig.3: No.41 Virginia Street. Fig.4: Volute with anthemion Fig.5: Courtyard Photo credit: © Cicerone

https://portal.historicenvironment.scot/designation/LB32795

37-47 (ODD NOS) VIRGINIA STREET CatA

Statement of Special Interest: “These buildings are important examples of a unified street and court complex and are the best remaining examples of their type and period. Early sign writing painted on to the ashlar from the 1820s survives in the doorway of No 37, including signage for the legal practice of C D Donald and Sons.”

Courtyard (REAR OF 37-47) LB32794 CatB

Statement of Special Interest: “The best street surviving unified street and court complex of the period.”

Curious that the main façade is catA but the courtyard only catB. Given the significant historical importance of this extensive colonial merchant complex should it all not be catA?

Anthemia: Scott would appear to favour the honeysuckle over palmate.

Robert Findlay’s descendants had a share in shipbuilders Paddy Henderson & Co. which had Burmese interests. These are referred to by Kipling in his poem ‘Mandalay’…”where the old flotilla lay” referring to the the scuttling of the Iriwaddy Flotilla Company. Originally formed in 1865 as the Irrawaddy Flotilla and Burmese Steam Navigation Co Ltd, primarily to ferry troops up and down the Irrawaddy River and delta. At its peak in the late 1920s, the IFC fleet was the largest fleet of river boats in the world, consisting of over 600 vessels carrying some 8-9 million passengers and 1¼ million tons of cargo a year. The ships, most of which were paddle steamers, were generally built in Scotland before being dismantled and transported to Burma for reassembly.1

The Virginia Buildings complex stretched from Miller Street through to Virginia Street totaling an expanse of over 30 bays. The north courtyard and Virginia Street are all that survive somewhat intact but much altered. The Virginia Street elevation comprises 10 bays in total. The centre 8 bays take up the entire plot that was detailed as ‘875 square yards of ground’ in the original feu of 1754 from George Buchanan of Drumpellier (2nd son of Andrew Buchanan of Mount Vernon) to John Bowman of Ashgrove (1701-1797). Bowman like his father before him was made Lord Provost in 1764-65. He was a merchant don of the elite class. A partner in Speirs, Bowman & Co. among other concerns. Speirs was his neighbour to the north in the plot now known as the Jacobean Corsetry.

The centre 8 bays match stylistically the interior courtyard. The wings at no.37 and no.49, possibly a later addition, appear to reference the Jacobean Corsetry to the north with the incised detail on the first floor windows. The wings have enabled the internal courtyard to be widened in order to utilise the enclosed space more effectively.

It is plausible that Scott was responsible for raising the height of James Dennistoun of Colgrain’s house at no.23 Virginia Street (the Jacobean Corsetry) to match the elevation of his newly erected Virginia Buildings. He appears to have had a close working relationship with the Dennistouns of Colgrain and this would have given him access to Sir John Soane’s work in Buchanan, Virginia and possibly Miller Street.

Robert Dennistoun was on the committee for the Theatre Royal Queen Street and was well known to Soane. The brothers had the ways and means to employ the very best modern UK architect to design their houses. And they do with the appointment of Sir John Soane a pioneer of Greek Revival in the UK. With such resources then at their disposal one cannot imagine the Dennistoun’s or Robert Findlay appointing a complete unknown to design an office complex for their extensive colonial operations. This would suggest the Virginia Buildings were not Scott’s first endeavour, simply the earliest we know about. After all, he had been operating his architecture academy for over a decade by this point.

List of Work: 2

Scott’s Practice

A feature of Scott’s practice in later years is that he employs an engineer with equal billing in the company name. There is some suggestion that he had some engineering training too. (1830 – 1833 He entered into a brief partnership with William Wilson, surveyor and engineer and c.1833-34 another with the civil engineer William Gale alongside architect John Stephen until 1839). This might explain why he is not more well known. Factories that had span, a need to be load bearing, fireproof, robust to cope with sheer stresses and strains alongside the general demands of industry would require a specialist knowledge. This may have been the niche that Robert Scott was filling.

An industrial practice would have been geared towards the anonymous foundries, factories, warehouses, engine works, shipyards and mills for his patrons. Doing the unglamorous work brings little chance of recognition. But it would appear his patrons did know his worth and when the need arose he was given license to design residential property.

Let’s not forget his patrons could employ Sir John Soane, Grand Master and architect to the Bank of England. So it is instructive that they appear to hold Robert Scott in such high regard. A sentiment backed up by both the Trades’ House & Merchants’ House.

Artist: courtesy of the Soane Museum

In 1827 the Tradeshouse required an audit of their lands. They engaged with four architects to carry out the survey:

Robert Scott (c1782 – 1839) In Glasgow directories he is listed as surveyor for the Trades House over numerous years.

John Reid Unknown. A William Reid (c1781-1849), architect, worked out of King Street Tradeston (1811-1829). Possible typo, more research required.

John Brash (c1775-1848) From New Kilpatrick

79 Stockwell St (1807-18),

Madiera Buildings, Argyle Street (1819-1828)

James Watt (c1789-1832) Possibly died in the Cholera epidemic of 1832.

(1811-1813) Practised as an architect based on south side of Argyle Street.

(1814-1820) ran an architectural Academy Argyle Street at Stockwell Street.

(1820-1831) ran an architectural Academy from Turner’s Court, Argyle Street. Watt was a member of the Philosophical and Dilettanti Societies.

The Merchants’ House of Glasgow,1831, in anticipation of a change in the law regarding the Cemeteries Act of 1832 sought to design a new cemetery at Fir Park modelled on Père Lachaise Cemetery in Paris. The Merchants approached two architects for a bridge design, ‘the Bridge of Sighs’. One was David Hamilton, the other Robert Scott. History only remembers the victor. Glasgow Necropolis officially opened in April 1833.

1824 The County Buildings, Dumbarton

County Buildings, court and prison by James Gillespie Graham (1766-1855). James Gillespie’s style was predominantly Gothic, however, here it is firmly neo-classical. Scott was employed to amend; no detail of extent.

Photo credit: Unknown

Scott had been working on the new Police Buildings in Albion Street, Glasgow early in 1824. Glasgow was at the forefront of Policing and advances in the civic approach to law & order in the UK. One suspects Gillespie wouldn’t have needed Scott’s help with classical orders, although the voluted capitals with anthemion necking look suspiciously like Scott’s work at Virginia Street & West Regent Street.

Was Scott sharing new ideas with Gillespie to facilitate coherence of the Dumbarton building with latest trends?

https://portal.historicenvironment.scot/designation/LB24875 catB

Statement of Special Interest: “The building has some fine classical detailing to its front elevation. Internally, the 1824 court has exceptionally delicate metal work to the gallery.”

The first floor centre bay with relieving arch appears as if it lacks proportion but is in fact the same size. The lack of a consoled cornice gives the illusion of being out of balance with both the wings and the imposing pedimented portico below.

Fig.8: OS 1859 map of Dumbarton with location of the County Buildings & prison. Reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland

1824 Central Police Buildings

Builder: James Govan ‘Craw Jamie,’ from his working the large quarry at head of Queen Street. (employed 82) Photo credit: unknown

We know from Thomas Rickman’s diaries of February 1824, who had been working on St David’s at the top of Candleriggs, that there had been interaction between Rickman & Scott concerning this building. (without having yet seen the entry I can only speculate what piqued Rickman’s interest.) Note what looks like ventilation plates under the windows of the top floor cells. (we see similar ventilation plates on The old Ophthalmic Institute at no.126 West Regent Street, unattributed, showing elements of Scott’s hand.) Also of note is the first bay on the south at Bell Street. Rusticated it looks like Scott is responding to Antigua Court opposite and tying in with neighbours on the main arterial route. It may also point to a more formal entrance on the south elevation for use by the general public as denoted on the OS map of 1857.

Fig.10: The Police Building’s entrance & quadrangle c1905.

Photo credit: unknown

Reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland

Under the former Police Acts the Board of Police were not authorised to lay out money in buildings, and were accustomed to pay an annual rent for such premises as they were able to procure. This was found by experience to be attended with much inconvenience, for it was difficult to find premises that were suitable either in situation, in extent, or in proper arrangement. By the act, however, of 1821, they are authorised to borrow a certain sum of money for the purpose of erecting buildings on a scale that might be judged adequate for the various and important uses of that establishment.

These buildings have just been erected, and are situated in South Albion Street. They form a quadrangle, and are 116 feet in length, 74 in breadth, and three stories in height. The principal entrance consists of a massive archway with Tuscan columns and entablature. At each end of the inner court, which is 50 feet by 28, there is a handsome entry and stair case, the one leading to the prison departments, and the other, which is constructed of a very hard and beautiful granite, to the Commissioners’ Hall, Committee Rooms, and other Public Offices. The upper or third floor contains dwelling houses for the superintendent and principal clerk, the remainder being occupied by wards for prisoners, and apartments for the superintendent of fire engines. In the first or street floor there are suitable offices for the superintendent and collector, accommodation for fire engines and water butts ; and a part of it is allotted for prisoners’ wards and cells. The sunk story is occupied with rooms for lamp globes, for oil cisterns, and for trimming lamps, a large hall for the watchmen, smiths’ and turners’ shops, heating apparatus, and various descriptions of cellarage.

The buildings are to be surmounted by a belfry, with an alarm bell to be rung in cases of fire. The architect, Mr. Robert Scott, has displayed great professional skill in the arrangements connected with this establishment, which must of course have been multifarious and complicated.

POLICE OFFICE: For Wardlaw and Cunninghame ‘Glasgow Delineated’ (University Press: Glasgow 1826) p.91

When you compare what replaced the early 19th Century work (See the later Police Buildings in Turnbull street built in 1904 by Alexander Beith McDonald. at a cost of £36,500 you get some idea why the earlier architects were so easily neglected. Plain & uninspiring by comparison. But Scott could be adventurous for his time.

1824 St Mary’s Episcopal Church, Renfield Street. ‘seats for 920’

Fig.12: St Mary’s Episcopal, Renfield Street b1824 dem c1874

Fig.13: Windsor Chapel. Photo credit: unknown

Fig.14: St George’s Tron. Photo credit: © Cicerone

Did Scott take confidence from his interactions with Rickman? Allegedly St George’s Chapel Windsor was used as his inspiration for St Mary’s. Gildard refers to St Mary’s specifically with faint praise, ‘of great merit, seemingly all the greater because built when the Gothic was, with us, not much beyond its infancy’. Crenellation today seems incongruous on a place of worship unless it’s fighting the good fight… ‘onward christian soldiers’. However, the minarets, ‘call to prayer’ seem a missed opportunity. One can’t help wondering what could have been if given more prominence in the overall design.

Possibly inspired by Lugar’s pattern book of 1815. See plateXXXII. Lugar was inspired by Thomas Danniel R.A. ‘Oriental Scenery’ 1795-1808 over six series. The 144 aquatints which made the complete set cost £210. (equivalent of c£18k today) A critical success, thirty sets were sold to the East India Company, and a further order for eighteen copies was received. (total sales approx £10k/£864k)

Equally the ‘minarets’ could be responding to the lightly capped cupola of St George’s Tron flanked by the four substitute obelisks, architect William Stark, 1807.

Scott can have James Cleland to thank for the Tron’s location after he had it moved from its originally intended site on St Vincent Street. When you compare his St Mary’s to mkII by George Gilbert Scott, St Mary’s Cathedral of 1871-1893, you can see how Glasgow Gothic matured. The spire of 1893 dominates what would have been originally a more sober design, more coherent to the modern eye than Scott’s original of 1824.

Engraver: Robert Scott, Edinburgh.

St Mary’s Chapel

“A new Episcopal place of worship under this name has just been erected in Renfield Street. The style is what has been termed the light or pointed Gothic, such as prevailed in the 14th or 15th century. The front extends about 96 feet, and the most prominent features are two octagonal towers, one on each side of the principal entrance, which rise about .30 feet above the roof. These are terminated by pinnacles in the form of mitres, with a cornice showing a band of roses, and decorated with crockets and finials. There are two lower towers at the angles, in which are placed the stairs leading to the galleries, in one of which there is a fine toned organ. The outline is taken from St. George’s Chapel at Windsor which is admired for the chasteness of its style and character. The architect is Mr. Robert Scott.”

Barony Church

“Erected in 1798, from a design of Mr. John Robertson, nephew of the celebrated Messrs. Adam, stands near the Cathedral and Infirmary. Its architecture is of a mixed style, and the outline of the west front has an imposing effect; but the execution of the exterior, which is done chiefly in rubble work, renders it a mean counterpart to the adjoining edifice, and has destroyed the effect intended by the artist.”

It’s obvious the author was unaware that when James Adam supplied the initial drawings for the Barony he did not wish to detract from the Glasgow Royal Infirmary nor the Cathedral precinct. (He certainly fulfilled that goal.) Moreover, in an exercise in financial prudence the stonework was specified as undressed. The design was not well received. So it’s curious that Robert Scott should attempt to resurrect the crenellated towers in his St Mary’s design. Viewed in isolation St Mary’s is still problematic. However, put up against the earlier Barony it is a marked improvement. Had he set himself the academic challenge of improving on the earlier Barony design? However, if one was being harsh you could say it wouldn’t have been difficult to achieve.

Reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland.

Episcopalian Benefactors

It’s interesting that Scott should design an Episcopalian Church given who his significant patrons were. Examining the early feuers of Virginia Street was like looking at a congregation of Episcopalians. Indeed, Alexander Oswald and David Dayell were on the management committee for Scotland’s first Episcopalian Church St Andrew’s on the Green. A committee that Alexander Speirs would later join. These ‘Virginia Dons’ were not just joined by business and family they were joined by belief too…at least in Virginia Street. Mungo Naismith’s story passed down, whilst working on his magnificent St Andrew’s in the Square, of seeing the ‘devil himself’ working on St Andrews on the Green is of legend. Shockingly, Andrew Hunter, one of the masons on St Andrews on The Green otherwise known as the English Chapel was ex-communicated when it was discovered he had worked on the build.

Would this have informed future decisions by Episcopalians to keep certain work within the faith so to speak? Could that have influenced architecture away from the solid baronial style of Mungo Naismith toward a ‘lighter’ more refined European style that we see develop later around the New Town. When you compare Colin Dunlop & John Murdoch’s houses to John Craig’s of Miller Street the architecture is more refined in the latter.

1825 Unknown, St Vincent Street.

In 1825 Robert Scott features in the Sasines for a building on the south side of St Vincent Street. The timing is curious in terms of what is known to be going on in Virginia Street; the last of the Virginia merchants of old are moving out and Findlay Duff & Co.’s business is facing significant headwinds. In 1825 the Dennistouns are still resident in Virginia Street but William Connal their partner has moved out to, 2 Milton Place, West St Vincent Street on Blythswood Hill.

By 1826 Matthew Brown, industrialist, has acquired 23(53) Virginia Street along with the Virginia Buildings.

JR Dennistoun and R Dennistoun & Co. The 1826 directory captures that they have moved to a house situated at 13 West St Vincent Street. Was Robert Scott the architect?

1827 Cameron House

The earlier house of c1750 was redeveloped for Admiral John R Smollet of Bonhill in 1812-1814 by James Gillespie Graham. In 1827, Scott was tasked with making amendments to Gillespie’s earlier work; scope & extent unknown. In 1866 after a fire William Spence rebuilt incorporating the library wing which remained. (painted ashlar denotes pre1866).

Over the centuries the Smollets hosted James Boswell and Samuel Johnson, the Empress Eugenie of France, Princess Margaret and Lord Louis Mountbatten, and Winston Churchill.

1828 Andersonian Institute

Scott was tasked with converting the old Grammar School on George Street with James Watt. Originally built in 1788, architect John Craig, by 1821 the school had outgrown the site and moved to adjacent premises. It lay empty until the purchase of 1827. There are no details as to specific undertaking but Huxton tells us the porch was introduced as the old building was Roman in style with only a rear entry. We can see that a third story has been added. What is not entirely clear is if the round auditorium was introduced at this point; most probably. The museum captured below suggests no expense was spared when it was enhanced in 1831 by James Smith of Jordanhill ‘amateur’ architect.

Fig.18: The Andersonian Institute. c1895

Photo credit: unknown (possibly Duncan Brown)

Fig.19: Image of Watercolour by John A Gilfillan, Professor of Drawing and Painting at Anderson’s University.

Gilfillan, in 1824, had his Drawing Academy at no.7 next door to Robert Scott at no.6 South Hanover Street. Gilfillan’s painting of 1831, shows the interior of the Andersonian Museum shortly after opening.

Fig.20: Fleming’s Map 1807 – Grammar School prior to conversion. Fig.21: OS Map 1857 – Grammar School after 1828 conversion & 1831 addition of museum Reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland’

Fig.22: Coloured cartoon from the “Northern Looking Glass” 14 November 1825 entitled “Rival Lectures: Anderson’s Institution” Sp Coll Bh14-x.8

Glasgow University Library, Special Collections

Fig.23: Old Lecture Hall, George Street. Reference: P2/1/17

Reproduced with the permission of Strathclyde University Archives

The photo captures the interior of the Andersonian Library at the Glasgow and West of Scotland Technical College in George Street, c 1890. Librarian George Martin is at the issue desk. This circular hall was once the Lecture Hall, and later the lower part of the Andersonian Museum.

The round wall seen in the cartoon would seem to confirm the round lecture hall shown above right. However, at this date the Andersonian Institute was still located on John Street (fl1799-1827). The round shape would have facilitated acoustics and viewing comfort. The roof lights would have provided advantages over a normal vertical window for natural light ingress. It would also appear that it was fitted with ’sparkling gas’ for additional illumination. (As was the Royal Theatre on Queen Street, the first UK theatre to be lit by gas.)

Fig.24: The Star Inn & Hotel, Ingram Street Fig.25: No.3 (later no.5 after 1826) John Street. Photos courtesy of Canmore.

Note the large pend on the south wing to provide coach access to the rear of the Star Inn & Hotel/(later Bank) on Ingram Street. The Star Inn sits directly east of Dugald Bannatyne’s house at the head of Glassford Street. His house was later consumed by it. His business partner (of the Glasgow Building Company), Robert Smith, architect for the Star Inn. The Institute architect unknown. (In 1804 Smith’s residence was John Street at George Street.)

Fig.26: The east face of the Italian Centre, John Street. Source: © Cicerone Fig.27: Hamilton’s Hutcheson Hospital b1805. Source: © Cicerone

The west façade of David Hamilton’s Hutcheson’s Hospital b1805 with the vertical wall of tri-partite windows intrigued me. This style of window was used extensively by the Glasgow Building Company around the new town in the early 1790s. Possibly being used here as a unifying element. However, I’d somewhat neglected to turn around and ask a question of the east façade of the Italian centre. Looking at Canmore raises the question, was Hamilton responding to the old façade of the Anderson’s Philosophical Institution Hall built c1799? (A key building of Glasgow’s enlightenment bought/built by Alexander Oswald of Shieldhall (1738-1813) c1799 from Hamilton, Fullarton & Co. for housing the Institute.) The Glasgow directory captures it at no.3 (later no.5 after 1826) John Street prior to the move of 1827 to the old Grammar School in George Street. The front we see today a possible later facelift. The south pend a later addition as it does not appear on the OS map of 1857, whereas the north pend is captured.

The arcaded ground floor is reminiscent of Robert Adams original scheme for John Street & Ingram Street that was replicated around Wilson Street and Spreull’s Land c1790. Here is the location where Birbeck would form his ideas that took him south to form the London’s Mechanics’ Institute. The record books record Glasgow built the third Mechanics Institute, however, up until that time it had no need for a ‘dedicated’ Mechanics Institute, it had Anderson’s Philosophical Institution Hall. For such a plain façade it is curious that Scott House its counterpoint on South Frederick Street facing west follows the same format though more elaborate. Seven central bays flanked north & South with (pilastered) tri-partite windows.

Fleming’s map of 1807 reflects a square footprint, (which could possibly accommodate a circular auditorium) but by 1857 the building has been repurposed, cut & shut, to create a courtyard to the rear for the Star Inn possibly to accommodate continued access to the stables that had been reoriented east west instead of the original north south. The Institute’s mutilation c1827 meaning that the plot lost any association with its provenance.

Fig.28: Fleming 1807 v OS 1857 view of John Street. Reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland

Extract from ‘The First Technical College’ 204 George street

“Considerable alterations were necessary to fit the old building for its new uses. A doorway was cut through the front and a porch erected so as to give entrance from George Street thus bringing the façade into the condition in which it is at present. Many internal alterations were made and a new building erected at the back, on what seems to have been the playground of the school. This building was circular in plan , 52 feet in diameter and was divided into two stories, the lower one being cited as a lecture room, with sitting accommodation for 400 auditors. In this room were delivered most of the popular lectures for which the Andersonian was famous. The upper room was fitted up as a museum; it was 30 feet high, covered with a fine dome , and was provided with cases to contain specimens. To allow of access to the upper cases a light gallery was carried round , which was reached by a flight of steps. In the centre of the floor was a lantern light for the lecture room below. Museum and lecture room were fitted from designs by James Smith of Jordanhill FRS who was afterwards president of the institution.

The above would seem to imply Scott was responsible for the front porch and internal refit. Though, the word ‘fitted’ above is curious as one would expect ‘built’ to be used. Was the work of James Smith a refit too of Scott’s earlier work? The cartoon above seems to suggest a round auditorium was preferred for lectures which suggest Scott may have introduced this from the outset at George Street. ( More research required )

Alexander Oswald of Shieldhall (1738-1813)

The property of Shield Hall (which contains over 300 acres), like many larger estates, is a collection of small properties, being made up of various of those “Bonnet Lairdships” into which most of the parish of Govan was once divided.

In 1781 Shield Hall was sold by Alexander Wilson’s creditors to Alexander Oswald, merchant in Glasgow, brother to George Oswald of Scotstoun.

Alexander Oswald of Shield Hall was a shrewd and enterprising man of business, and was engaged in various undertakings besides his own foreign trade. He was a partner in the South Sugar-house Company with Casper Claussen, a Dutchman, as managing partner. He became sole proprietor of M’Ure’s “Great Work” for the making of ropes, and built the tall tenement with a rope carved round it, which stood till the other day at the corner of Ropework Lane. And he was an early and successful investor in building ground. (2) But from the leading business of the day he held aloof. He had tempting West Indian offers, but he refused them all : he would not, directly nor indirectly, mix himself up with slavery.

Rigid in his own expenditure, he was a generous though discriminating giver and lender. Though a grave silent man, he was full of humour and information. He took a keen interest in the Andersonian University, and in every appliance for spreading knowledge. He was one of the founders of the Royal Infirmary.

In days when it was not pleasant to be a Whig, he was a Whig, or perhaps a little more. For he said about the French Revolution much what most people now say, and he openly denounced the wretched Dundas system of government, and favoured a Reform Bill something like the old measure of 1832.

He could almost walk on his own ground from his office in Ropework Lane off the Stockwell, to his house, in Madeira Court, at the head of Oswald Street. It was the westmost of the two detached mansions that formed the Court. Oswald Street is built on what was Mr. Oswald’s garden and field.

Back to Robert Scott…

1830/31 West Regent Street (nos.172-186 & no.188)

The anthemonia necking of the ionic pilasters at 116 Blythswood confirm Scott’s link with Virginia Buildings (see Figs3&4 with Fig.14 below for comparison). It suggests Scott wasn’t afraid to re-use designs to keep cost down. Was this pragmatism part of his appeal for the Tradeshouse?

Although he does switch it up on the main south façade with the pulvinated doorcase that has echoes of the Thomsonesque entry at no.95 further down. Does his dispensing with a porch here at no.188 suggest a desire to maximise light into the hallway…. and/or does the stone discolouration of the door case suggest a clever remodel at some point by another hand? I suspect the later.

At 176, 180 & 184 the (Victorian) porches of ‘neo-medieval proportions’ are problematic. Originally there would only have been two double main street entrances, at 176 & 184. They would have been grand double wide stairs possibly similar to what existed at Blenheim Place of 154 West Regent Street. Entry 180 was merely a means to access the turnpike stairs to the rear. At some point both houses have been divided up and 3 new single entries created. The oversized porches and paint simply hide the scars. The Greek key is I believe original at 176 & 184 (crisper & more defined than 180) a nod to Soane’s use of the motif. Scott would have been very familiar with his work in Glasgow given his association with the Dennistouns’ of Colgrain. Do we have Scott to thank for keeping Greek key vital in the city?

The approach to Blythswood square would benefit from reinstating 172-186 back to how it was envisioned with paint removed.

Fig.30-32: 116 Blythswood doorcase. Source: © Cicerone Figs.33 & 34: 176-180 West Regent Street. Source: © Cicerone

c1835 West Regent Street (no.126-128) un-attributed

The old Ophthalmic Institute at no.126; has managed to retain the original portico. Entablature and ionic columns & pilasters feature ionic detailing very characteristic of Robert Scott’s hand. Canmore captures on its website older pictures still reflecting ventilation plates similar to those on the South Albion Street Police Buildings.

Photo credit: © Cicerone

c1835 West Regent Street (no.152-154) dem un-attributed

Also known as Blenheim Chambers but was originally Blenheim Place has Scott’s characteristic detailing on cornices. Canmore captures interior view of ceiling, south east room, ground floor with intricate plaster work.

( No.113: Whilst the porch appears to be a later replacement (James Thomson?) the consoled architraves on the façade look very similar to those at Dumbarton County Buildings. However, they are not a perfect match, as in the case of the anthemia elsewhere in the street, which are duplicates of other known work. )

It throws up the possibility that Scott was responsible for far more of West Regent Street than previously thought.

Fig.36: OS Maps 1857 & 1892

Reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland.

1831 Bothwell Parish Church

Working possibly as a clerk of works for David Hamilton at Bothwell Parish Church making amendments to the Nave in the new Church west of the medieval Choir complete with Hamilton Monument.

1834 Boturich Castle

Boturich Castle Loch Lomond, by Robert Lugar 1830-32 for John Buchanan of Ardoch. The Castle was built on the site of the previous 15th Century castle. Boturich Castle belonged to the Lennox and Buchanan families originally. 1834 additions by Scott, Stephen & Gale. In 1850 the Octagon Tower, to the left of the photo was added and became the principal entrance. Again we see Scott being brought in after the main build. Is he fixing settlement issues or ‘problems’ not envisaged in original plans or introducing ‘modern’ comforts. The truth is we don’t know. …But, possibly, he was recommended by Smollet after his earlier work at nearby Cameron House.

© George Rankin CC BY-SA 2.0

1838 Gartsherrie Parish Church

By Scott, Stephen & Gale. Gothic Revival with clock tower & steeple.

Completed in 1839 for the benefit of the workers employed by Wm Baird & Co, ironmasters, and their families. It borrows on James Smith of Jordanhill’s Govan Church of 1826 which itself was referencing Shakespeare’s the Holy Trinity Church in Stratford-Upon-Avon.

Photo courtesy of David Warden ©

1838 The Queens Tea Store, 23 York Street

Commissioned by William Connal, I believe this to be the William Connal of Findlay, Duff & Co. or relation. Thus maintaining the strong mercantile links from Virginia Street. Of note is the inverted ‘crenellation’(corbals) & chancery-esque windows with elements of ‘Rundbogenstil’ inserted into a fireproof castillo.

Figs.39-42: 23 York St, Source: Canmore

Reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland.

pre 1839 Buchanan Street

Thomas Gildard (1822-1895), who was articled to David Hamilton 1838-1843, at the end of his career in 1895 wrote an article on some old Glasgow architects for the Philosophical Society. In the piece he has the following to say about Robert Scott:

‘A firm in practice of the time I speak Scott, Steven & Gale. …Mr Scott seems to have been a ripe architect, whether of much originality or not, certainly of much culture. A building by him in Buchanan Street nearly opposite the Arcade, and since destroyed by fire, was quiet, yet dignified in composition, and elegant in detail, and, although by no means obtrusive was seen to be the work of a man who thoroughly knew what he had to do.’

I have written about the possible location previously with reference to Soane. Though I now suspect it was possibly in a range of buildings not simply one as evidenced by who resided at plots 4-6 Buchanan Street and his work in Virginia Street and West Regent Street.

The Greek key motif extant at no.79 Buchanan Street for me links Scott from this location to the porches in West Regent Street. The porches are not original (Victorian) but contain original elements at nos.176 & 184. (I contend this location in Buchanan Street is the actual site of Sir John Soane’s house for Robert Dennistoun; Mitchell Lane a remnant denoting the old access to rear stables.)

71-79 Buchanan Street today. (Note the window misalignment from the 2nd floor up as a result of the 1887 fire.(Not to be confused with the earlier fire that Gildard refers.)

Figs.44 & 45: 71-79 Buchanan Street with Greek Key. Source: © Cicerone

His Influence: who did he teach?

In October of 1847 Alexander Watt LL D., (c1796-1847) city statist & cathedral warden, Professor of Astronomy at Anderson’s University (1828-34) died. In his obituary it states,

“ Dr Watt was a native of Glasgow, and was educated as an architect and engineer under the late Mr. Robert Scott, and for a brief period practised his profession, as successor to the late Mr Denholm.”

The Glasgow directories support this, where James Watt initially appears in 1811 as an architect at 164 Trongate. By 1814 a J&A Watt are running an architecture academy from 9 Argyle Street. This suggests Alexander and James are in partnership but only very briefly as by 1818 James Watt, architect (c1789-1832) is running the academy solo whilst Alexander has taken the (more prestigious) position replacing James Denholm at Glasgow Academy.

The obituary might infer that James Watt was taught by Alexander or by Robert Scott directly. If indeed James Watt and Scott ran separate branches of the same academy that would point to Scott as being head of the lineage. (However, it cannot be ruled out that the two schools were distinct.)

The obituary, almost eight years after Robert Scott’s death gives some indication as to the esteem Scott was held in his day. It also informs that Robert Scott had some engineering ability which is borne out by the public and private builds that we can attribute to him.

His Influence: in Partnership

If some Greek key and anthemion could be said to influence its impact is negligible when compared with the contribution of John Stephen (c1807 – 20 Nov 1850) who joined Scott in partnership from 1834. Scott one would assume provided a nurturing hand, but possibly didn’t give the free reign that say a Honeyman & Keppie would later grace Macintosh with for the GSoA. Maybe not as much a reflection on Scott as a reflection of the time. Gildard described Stephen as:

‘An architect of great promise [who] early taught us the elasticity of Greek architecture’ and ‘exercised his gifts as if he felt he was responsible for them’.

We can also infer from this statement that Scott new talent when he saw it. For that we must be thankful. (Enough raw material would have passed under his watchful eye over the course of thirty years.) After Scott’s death Stephen would continue working from 23 South Hanover street from 1839-1844. When looking at some of his work that was begun in partnership with Scott (& Gale) but finished solo one sees a flourishing of ideas that simply had not been present earlier. (At least not from the evidence that remains.)

The Napoleonic campaigns in Egypt between 1798 and 1801 had ignited a fascination with all things Egyptian in Europe and the US. By 1825 we get a sense of how strong its hold was in ‘North Britain’ and especially Glasgow (see the Looking Glass, issue one, 11 June 1825). In that period in terms of decoration we only see Scott having a preference for honeysuckle versus palmate anthemion, if anything he was more Greek, following Soane’s lead with Greek key. When Scott did stray from his restrained neo-classical work it was to Gothic.

As others have noted a key influence was what was happening in the art world:

“Artists like John Martin (1789-1854) produced grand works which portrayed Biblical history in an apocalyptic light. In paintings like Seventh Plague of Egypt (1823), Martin drew on illustrations of Egyptian monuments to depict a Biblical scene, showing Moses calling down a plague upon Egyptians and the pharaoh. This work was an attempt to use Egypt to display the emotion and drama of the Biblical narratives.”

If the number of different congregations and proliferation of Churches in staunchly calvinist Glasgow was anything to go by then the city was ripe and ready to consume any biblical message. Any. Combine this with a burgeoning art scene with both old and new money and one can see how the zeitgeist can then be said to inform the architecture. It’s instructive to note the time lapse though. Martin was producing this themed work in 1823. Stephen doesn’t introduce into his work until c1838. The ideas would have taken time to percolate, distil and wait; for the freedom to execute something ‘new’.

Figs.46 & 48: St Judes (catB). Source: © Cicerone Figs.47 & 49: Sighthill Cemetery, 201 Springburn Road (CatB) . Unknown & Duncan Brown

The overtly Egyptian St Judes of 1838, 278-282 West George Street (catB), where we see an idea extrapolated to fixtures and fittings. And again, Egyptian was to the fore on the competition winning Blythswood Testimonial School. His vision for Sighthill Cemetery of 1839 not content with waiting until you approach the Chapel (complete with an Egyptian winged sun disc over the doorway), the entrance gateway clearly signalling a different realm.

Other examples of his work: the neo-classicism of Customs House catA where he may have been involved with John Taylor. The pragmatism of Dundas Street Station (Queen Street Station) built for the Edinburgh and Glasgow Railway, opened 1842. And his utilitarian warehouse in James Watt Street c1847. The anchor & barrel, very matter of fact. Juxtaposed with the over sized anthemion, whose scale Peter Nicholson, architect of the Hamilton Building at the old College, b1811 would be proud. If one looks at the Sighthill Chapel, St Jude’s and the James Watt warehouse as a collective; Stephen didn’t hold back when it came to roof ornamentation.

Figs.50 & 51: James Watt Street warehouse c1847 by John Stephen. Source: © Cicerone

His Sphere of Influence

Inferred by location/proximity:

1809-1812 626 Argyle Street shared address with James Haldane, engraver.

1815-1819 2 Argyle Street next door to James & Alexander Watt Architecture Academy

1815-1819 2 Argyle Street, opposite John Shepherd & John Baird I at foot of Virginia St

1822-1825 4 South Hanover Street, John Herbertson occupies address Scott vacated previous year 1821

1824 6 South Hanover Street next door to J.A. Gilfillan Drawing Academy

1826-1827 19 South Hanover Street, John Herbertson next door to Scott at no.23

John Herbertson (1789-1854) working next door to Scott for 6 years might suggest a working relationship. We do know he was articled to David Hamilton (1804-1805). (As a matter of interest David Hamilton had previously resided in South Hanover Street a few years earlier.)

By 1822 Herbertson was architect to the Lanarkshire Prison Board when he designed the Glasgow Bridewell in Duke Street. Does this explain Robert Scott getting involved with both Dumbarton Prison and the Central Police Buildings? Scott moves out of 4 South Hanover for Herbertson to move in. The appointments possibly necessitating both working side by side. John Baird II was an apprentice of Herbertson from 1832 and John Carrick an assistant from 1826 to 1839.

Inferred by ‘articles’

pre1814 Taught Alexander Watt architecture and engineering (& possibly James Watt)

1830-1832 John Baird II apprenticed to James Watt (1789-1832) later to John Herbertson (1789-1854) worked with John Fisher until Spring 1837 when he joined David and James Hamilton where he was very unusually allowed to put his name in the Directory.

1850-1854 Alexander Gordon Watt (born 3 Sept 1824, Glasgow son of James Watt of the Academy.) Articled to William Spence. In practice with Hugh & David Barclay later James Sellars: (David & James members of Alexander Thomson circle.)

c1884-1888 Alex Watt working from 131 West Regent Street. A street with its fair share of both artists & architects in residence. (I’ve noted numerous architects working from this street. GFS captured the artists as part of his research.)

The Final Years

In the 1836 Glasgow Directory we see Scott residing at 72 Norfolk Street, Lauriestone. A couple of blocks from where Alexander Thomson would later erect his majestic tenement on Gorbals Cross. He was buried on 20 April 1839, intestate. Claims were made on his estate by nieces and nephews and from this we are able to extract a precious few final clues as to who he was.

Debt owing to defunct Western Bank of Scotland

Proceeds house furniture by auctioneer John Donald

Proceeds from sale of books Barclay & Skirving auction

Claim against managers of St Marys Chapel

Debt due by late John Gordon of St Croix

Scott, Stephen & Gale share of outstanding debt

Robert Darling, Lesmahagow

Rents due for half year as follows:

Mr Angus Spirit Dealer Stockwell St.

Mr Adam tenant in Craigannet Stirlingshire

John McConchie tenant Craigneuk half year salary at

Whit_less school masters salary and deductions

Due by John McClymont house factor Glasgow

Allan Fullarton Esq ground annual Butterbiggins

£367.8.9

£45.17.10

£33.3

£50

£299.11.9(£150)

£172.10.1(£100)

£47.10

£13.5

£56

£18 £31.10(£-) £19.13

If looking at the sale of books, in today’s terms that would amount to £4,380. A bibliophile.3

No tangible property appears, does this suggest it was sold to pay off the Western Bank of Scotland? In annual rent he was collecting the equivalent of £23k in today’s terms.

The debt due by John Gordon of St Croix; It would appear Scott had been boarding, clothing and schooling Gordon’s son. In real terms today that is the equivalent to an outlay of £28k! (Written down to £14k.)

His business partners owed him the equivalent of £16k. (written down to £9k)

Robert Darling was the husband of his niece Marion Scott. All of his nieces and nephews with their respective spouses resided mainly in Lesmahagow & Carmichael. One of his nieces Janet married John Miller possibly of Hillhouse, Lesmahagow. The fact only nieces and nephews are noted suggests he had no immediate family, or at least none still alive. In the absence of any other supporting documentation nothing else can be inferred accept that he may have had close ties to the area. (‘Scott’ as a name has a stronghold around Linlithgow and the borders.)

In the 1868 Stirlingshire directory there is a George Adam residing Craigannet Farm in St Ninians. He died 16 April 1898. The Kirk O’Muir cemetery lies on the northern slopes of the upper Carron Valley just over one mile west of Easter Craigannet, one of the many farms worked by members of the Adam family. Possible Mr Adam is the father of George; his parents were David and Elizabeth.4

As for Allan Fullarton, there is an interesting overlap with Scott’s known work. One John A Fullarton of A Fullarton & Co. resided at 180 West Regent Street in 1839. Possibly the son of Archibald Fullarton who ran the publishers and engravers of Glasgow 1833-40, of London, Edinburgh and Glasgow 1840-43, and of London, Edinburgh and Dublin and London from 1845. They maintained a prodigious output of books, atlases and maps.

Allan Fullarton may be the same Allan Fullarton who along with James McHardy [Sheriff Clerk Depute of Lanarkshire] bought 4 Woodside Place in 1829. His house was listed as Woodside Cottage but by 1839 in the directory there was Allan Fullarton listed commissioner for four courts of Ireland, 76 St Vincent St, ho 4 Woodside Terrace. Later moving to 19 Woodside Place by 1866. A Butterbiggins Cottage is captured on OS maps of 1857 & 1914 south west of the Southern Necropolis. In the directory of 1843 a Mrs Robert Watt, Butterbiggins, mid cathcart rd is captured whilst in the same year a Robert Watt of customs house, 92 West Regent Street. Butterbiggins would later be consumed by Larkfield Bus depot:

Fig.52: OS Map 1914 & 1857 Butterbiggins Cottage

Conclusion

Robert Scott was obviously versatile and could respond sensitively to the locale when required as evidenced by the Virginia Buildings. So successfully there as it happens that it has confused many as to the true build chronology with the Jacobean Corsetry. Scott I suspect cleverly introduced both the balustrade to tie in with the Virginia Mansion to the north and introduced the blind relieving arch to mirror the adamitic tenement on Wilson Street. The success of these not only enabled the Corsetry to blend in with the existing urban realm but crucially hid the Corsetry’s true residential origins. But he didn’t always produce the most elegant work, although there are signs in West Regent Street that he attempted to enhance the approach to Blythswood Square with understated neo-classical grandeur. His style restrained; pragmatic does not win plaudits. And that is where his reputation possibly lost ground. Without fully appreciating that he was a keystone of architecture teaching for over a quarter of a century, fulfilling simply two from a three of ‘Firmitas, Utilitas, Venustas’ has proven not enough, especially, in a city that was so blessed with excellence in all three spheres. However, his impact should not be underestimated. Teaching successfully necessitates a generosity of spirit. Regardless of the lack of specificity surrounding his provenance or who he taught or who was ‘articled’ to him those thirty years cannot be ignored. He was surveyor for the Trades House and called upon by the Merchants House. He was one of the trustees of the Haldane Academy Trust a precursor of the Glasgow School of Art. One gets the sense he did not have the ego or ambition of a David Hamilton or Peter Nicholson but neither did he have their eye. However, due to the solid technical foundations he laid, his legacy to the built environment of Glasgow, ‘owing something to the influence of Soane’ ought to be remembered.

- Only in Glasgow can you in the space of a courtyard transition from Kipling to the bard himself, Robert Burns. The tenement in Virginia Street having been home to one of Burns’s Mauchline Belles for twenty-five years. ↩︎

- https://www.scottisharchitects.org.uk/architect_full.php?id=203457 ↩︎

- https://www.officialdata.org/uk/inflation/1839?amount=33 ↩︎

- http://www.burgesses.info/taylor/kirk_o_muir_cemetery.html ↩︎

© Cicerone: MerchantCityGlasgow. All Rights Reserved 2023