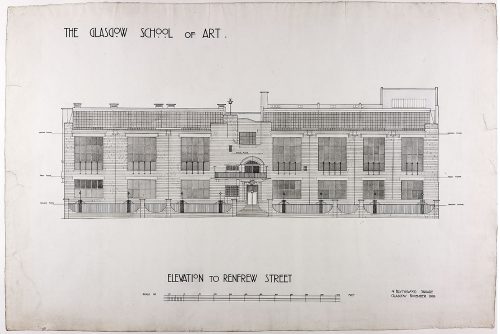

Architect: Charles Rennie Macintosh b1896.

Photo: © Alan McAteer

The institution recognised as the GSoA was formed out of an amalgamation between the Government School of Design and the lesser known but no less important Haldane Academy Trust.

Glasgow’s Government School of Design, founded in 1845, was originally located at 12 Ingram St, just west of Montrose Street in the former townhouse of Andrew Buchanan of Ardenconnel. The Academy’s goal was to nurture commercially viable designers who could be utilised to improve the appeal of locally manufactured products.

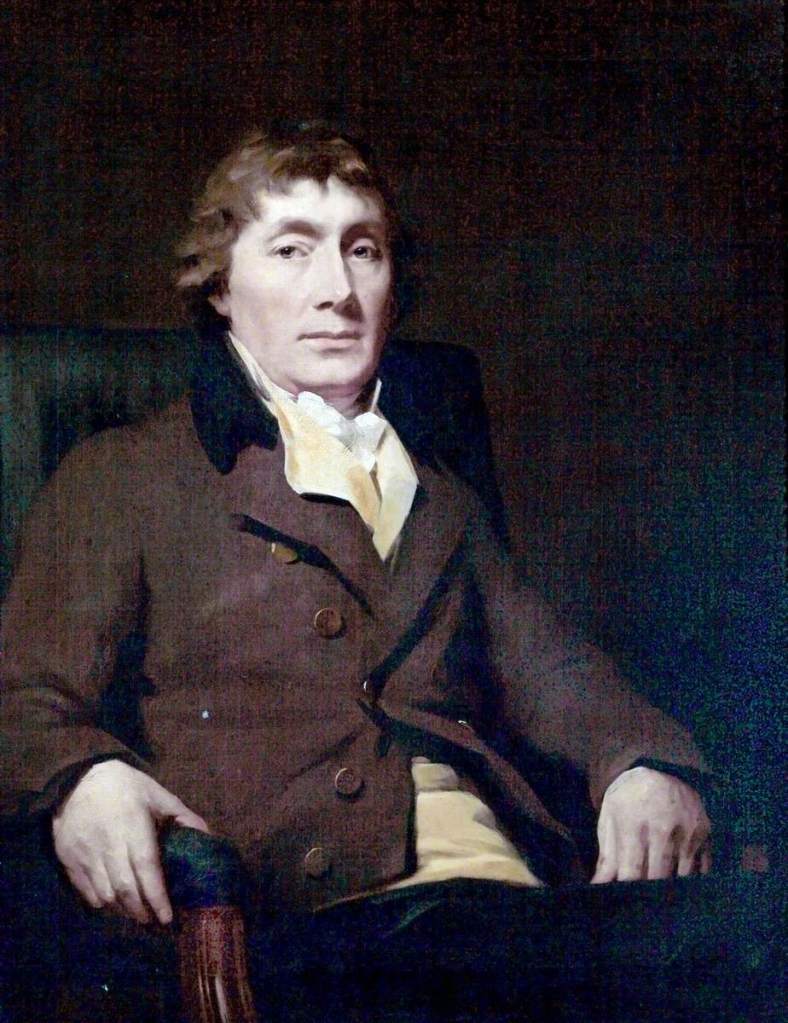

Andrew Buchanan of Ardenconnel (1745-c1834)

Andrew Buchanan of Ardenconnel was the second son of Archibald Buchanan of Silverbanks (one of the early feuers in Virginia Street whose house would later become the Thistle Bank.) Andrew was married to Jane Dennistoun the daughter of Jame Dennistoun 14th of Colgrain. Each of her three brothers were patrons of Sir John Soane in Glasgow.

From c1801, 74 Ingram Street (from 1827 no.12) was the location of his city townhouse. Fleming’s map of 1807 captures quite a significant footprint for this townhouse on Ingram Street that was reputedly only seven years old.

The architect for this townhouse is not known but the weigh house of 1785 that sat directly adjacent on Montrose Street is attributed to architect William Hamilton. (Renwick vVIII. Hailing from London, but of Scottish descent, what little remains of Hamilton’s work in the city deserves to be better known.)

Reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland

Reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland

The OS map of 1857 clearly captures ‘Government School of Art’ on the south west corner of Montrose at Ingram Street. The Buchanans vacated their townhouse c1809, one assumes, to retire to Rhu.

Architect: David Hamilton c1800

Photo credit:unknown

The east wing an addition between 1860-1896

John Dunlop’s townhouse location has a curious claim to fame. There cannot be too many sites in the UK where one owner has engaged Robert Adam for a subsequent owner to engage Sir John Soane and for any of that work to remain. I’m not aware of any other location in Scotland other than at 53 Virginia Street, Glasgow; ‘the Jacobean Corsetry.’

In 1983 Alistair Rowan wrote about Robert Adams designs for ‘Sunnyside’ a commission by Sir Patrick Inglis of Craigs and ‘Rosebank’ for John Dunlop of Rosebank, a Lord Provost of Glasgow. Others have noted the evolution in these earlier Adam designs and what David Hamilton produced at Ardenconnel for the Buchanans.

Charles Mackean has pondered if Hamilton knew about and/or had access to Adam designs. (Hunterian Museum, Glasgow University – Hamilton Drawings GLAHA 42915-7)

I originally thought one conduit might have been Robert Morison (c1748-1825) who worked in both the Adams and Soane practices and built nos. 26-30 Howe Street, Edinburgh. However, another suspect has come into frame who will be the subject of a later article.

Dumbartonshire, Sheet XVI – Survey date: 1860, Publication date: 1865

Reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland

We can get an idea of the the scale of the Rhu property, lands & outbuildings from a survey of 1860. It is, again, one of the largest properties in the vicinity. The outbuildings(offices) as they are today give some idea of how it may have looked in the early 1800s, a bucolic estate by the coast. Helensburgh was conveniently situated nearby on the north bank of the Clyde.

Figs.9 & 10: Outbuilding/Offices, Ardenconnel House. Photo Credit: unknown.

The established wisdom would suggest that the Buchanans built both their townhouse and re-constructed Ardenconnel c1800. One suspects they may have had the means to have undertaken both builds simultaneously given their financial means. However, an alternate hypothesis might suggest that the sale funded the improvements at Rhu.

In a case of ‘like father like son’ in May 1809 the townhouse at no.74 became a branch of the Glasgow Bank which operated from there for the next 35 years.

Then in 1845 the house switched from being a mercantile concern into an artistic one; a school of art.

Copyright. Reproduced with the permission of GSoA

The Haldane Academy Trust

The city had made prior forays into the teaching of the fine arts. George Fairfull-Smith (GFS) has written extensively about the progression from the Foulis brothers Fine Arts Academy fl.1752. He identified it was the first UK institution to provide students with scholarships to Italy. Ahead of its time in Scotland (& UK), the closure of the Academy in 1774 was not a surprise to the Foulis brothers’ friends and benefactors. However, its demise left a vacuum.

GFS catalogues the subsequent private initiatives, arts courses within multi disciplinary institutions and annual exhibitions that kept the arts alive in Glasgow but none would quite match in scope, scale or longevity the earlier Foulis Academy. It would take over 50 years for the arts to find a firm foundation again.

Fig.12: ‘The Wealth of a City’ 2010, author George Fairfull Smith

In 1833, a founder member of the Glasgow Philosophical Society, James Haldane, engraver, would attempt to support the arts on a more formal basis when he and his wife Agnes Thomson (of Faskine & the Thomson banking dynasty) established the Haldane Academy Trust to develop the study of fine arts in the city.

Haldane’s trustees as listed on 14 June 1833, were divided into three classes each of 25 men:

- 1st: merchants, manufacturers, and bankers

- 2nd: professional men, tradesmen

- 3rd: painters, sculptors, engravers, carvers and gilders, architects, modellers.

The stratification follows an approach taken earlier by John Anderson University management which ensured representation from a cross section of 50% of the city’s elite.

Fig.13: List of Haldane Academy Trustees by ‘Class’ Source: Dominic D’Angelo https://greekthomson.substack.com

James Haldane (c1767 – 1843)

There is no information regarding James Haldane’s formative years. Born in Kilmaronock near Balfron, not far from Airthrey Castle with historic links to the Haldane name, he was probably apprenticed aged 11 or 12 and bonded for the normal 5-7 years before graduating as a journeyman printer.

As such he would have been working for a few years when at the age of 22 he was listed as ‘Haldane J. and Co. engravers and copperplate printers, Argyle Street’ as captured in the directory of 1789. Up until this period only a few engravers had been documented in Glasgow:

1778: Andrew Readie will, ‘engraver in Glasgow’ cc9/7/70

1783 Alex Baillie engraver, Trongate

1783 William Edwards engraver, Saltmarket

1783 James Lumsden engraver, Trongate.

1787/89 James Lumsden, 2d flat Craig’s Land at head of Old Wynd.

The printers in 1789 were listed as:

1789 William Bell, printer top Gibson’s Land Saltmarket

1789 Alexander Adam, printer north side of Prince’s Street

1789 Chapman & Duncan printers of Glasgow Mercury McNairs BackLand Trongate

1789 Robert Duncan printer, Gibson’s Close Saltmarket

1789 Andrew Foulis, printer, Shuttle Street

1789 David Niven, printer, first Close Gibsons Wynd, Saltmarket

1789 James & Matthew Robertsons, printers, east Saltmarket no13

1789 Peter Tait printer of Glasgow Journal, shop Saltmarket no11

Given Glasgow’s geographical location, amongst other factors, printing was introduced late to the city. The established history is that 1638 heralded its arrival when the Church of Scotland brought printer George Anderson for their General Assembly. He was succeeded by his son Andrew. The Commissary Court of Edinburgh, February 1681, captured one ‘Alexander Cunyngham, printer in Glasgow’. Later in 1706 Bessie Corbet relict of ‘Robert Sanders printer in Glasgow.’ Loneliness is a killer. After a slow start, as the 1789 directory attests, things had begun to improve.

It’s interesting to note the procession of printers in the intervening years, from the historic areas around the High Street, Saltmarket and old Collegiate Church of St Mary and St Ann on the Trongate (now known as the Tron Theatre) toward Virginia Street and beyond.

Enticed by the new ‘god’ banking it would not be church but commerce that requisitioned the city’s printing services. One of the city’s eminent paper makers Edward Collins & Co. had their paper warehouse on Virginia Street (situated north of where Melvin & Leiper built their Italian palazzo (b1867) for the Glasgow Gas Company. South of this building the Thistle Bank was founded 1761. It held the distinction as the longest banking site in the city up until the mid 1800s. One can hypothesis that Edward Collins & Co. locating in Virginia Street was no accident as it would have provided the bank owners control and some security to mitigate against forgery.

One of the very earliest forays into early lithography in Scotland were conducted in Virginia street c1821 at Cleland’s Land, (now a hole in the ground masquerading as a carpark for over fifty years.) And by c1834 we see Glasgow’s first steam powered printing press being located at 65 Virginia Street home to the University Press of Edward Khull jnr. It was his German father who had previously been in partnership with Blackie & Co.

Khull jnr would later emigrate to Australia and be a founder member of the Melbourne Stock Exchange having married a distant relation of the Dennistouns of Golfhill. Indeed the farmstead his family initially stayed at in Australia was called ‘Golfhill’. One of Khull’s employees from Glasgow, the inventor, legislator, publisher, printer James Harrison(1816-1893) would found the Geelong Advertiser now the 2nd oldest print publication in Australia. He was the son of Glasgow poet William Harriston, author of ‘the City Mirror’.

1799 through 1801 Haldane is listed as, ‘J Haldane Donalds Land Trongate’. Reputedly the birthplace of Sir John Moore who is commemorated in George Square. Donald’s Land was situated at no.154, (later no.88) Trongate just opposite the Tron steeple, an early centre of printing in Glasgow. (Denoted by the horse riders head in Fig.14 below.)

Reproduced with the permission of Glasgow City Council, Glasgow Museums

In 1802, Haldane was chosen by the newly founded Glasgow Philosophical Society to engrave their membership certificate, Haldane would have been moving in the brightest of circles within the cognoscenti of Glasgow.

From Trongate, in 1803, he moves west to 626 Argyle Street which at that time was on the south east corner of Miller Street, north side of Argyle Street. (the street would renumber in 1826 when 626 became no.42) The location appears to be on the old plot of John Miller of Westerton who projected the street.

A John Miller Esq was on the committee of the Haldane Academy. This might either be his son (1778-1854) which is most likely given the name appears in the first rank or possibly one of the printers ‘John Miller’, died (1837/42/47) For some reason in 1806 Haldane relocates back to the Trongate at no.154 (Donald’s Land) for a year. Then he returns to 626 Argyle Street which he occupies for the rest of his working life.

It’s interesting to note that following his death this site would be occupied as a printers and lithographers for at least the next half century. John Brown jnr, William M Martin and then around 1888 Horn & Connell, Printers, 42, Argyle Street, and 12, Miller Street.

The continued use of the building as a printers for over 85 years was not unique to 626/42 Argyle Street. It was a pattern of use that was repeated at several addresses for draughtsmanship, printing, lithography, architecture and later photography. But it might appear that Haldane locating here was a catalyst for other like minded artisans and artists to congregate in the area.

Printing & lithography are not the only remarkable fact about this location. It was also the address from which Robert Scott (c1782-1839) ran his Architectural Academy between 1809-1813. Robert Scott holds the distinction, from 1803, as running one of the city’s first dedicated commercial architecture schools that we know about.

The fact that both Haldane & Scott were operating from the same address for almost five years suggests both would have been known to each other and possibly one of the reasons for Robert Scott’s inclusion in Haldane’s list of trustees alongside fellow architects David & John Hamilton, John Herbertson and John Weir. Scott would have had years of experience in teaching architecture and mechanical drawing outside of practice and as a bibliophile enough resources to draw upon. As such, his inclusion suggests continuity in the teaching of architecture in the city.

Haldane operated from this location for over twenty-five years. Robert Scott’s Academy must have been successful too. It operated at various locations in the ‘Merchant City’ for over twenty-five years. Another Architecture Academy run nearby by James Watt (a possible pupil of Scott) began in 1814 at various addresses along Trongate and Argyle Street before finding a permanent home in Turners Court in 1825 which was located close by on the other side of Argyle Street. An architecture school would be run from the court until 1832, possibly 1839, before continuing as a printers into the 1890s.

Reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland

The area around the foot of Miller Street and across Argyle Street into Turners Court at 87 Argyle Street, and also, between Maxwell Street and Dunlop Street appears to be an enclave of artisans and artists right in the heart of the monied new town.

For example Alexander Finlay, carver and gilder ‘print seller to His Majesty’, originally had a shop selling prints at 144 Trongate 1807-18. He would allow letters to be left there. In 1814 we see architect David Hamilton and later in the 1817 directory Peter McFarlane, plasterer, requesting letters be left at the address. So it is no surprise that his next location is in Argyle Street at the foot of Miller Street. With now a dedicated picture gallery in nearby Maxwell Street.

The close proximity of artists and artisans would have facilitated the sharing of resources, knowledge and ideas. And of course offered proximity to potential clients. Another Glasgow architect was located close by.

From 1803 until 1817, John Shepherd, was operating a few doors east at no.636 Argyle Street as architect and agent for heritable property. He would have been well placed at the foot of Virginia Street to serve the merchants and aristocrats residing in the neighbourhood. In 1815 he took on a relative as an apprentice by the name of John Baird, then aged 15 years. He would become known as ‘Primus.’

After Shepherd death in 1818 for the next ten years until 1827 John Baird I (1799-1859), architect, was located here at 636/22 Argyle Street before moving to 5 Buchanan Street in 1828. This confirms an architects office was located here at no.636, continually, for 25 years. Baird would have seen at close quarters the construction of Robert Scott’s ‘Virginia Buildings’ and possibly the alterations made to Soane’s ‘Jacobean Corsetry’ at no.53 Virginia Street.

28 Argyle St would later in 1844/6 be the site of Wylie & Lochhead’s innovative department store. We are led to believe that Lochhead, a trained cabinet maker, in the capacity of architect came out of nowhere and immediately built a superb multi-story commercial property employing the latest advances in construction, using cast iron, whilst at the same time running a rapidly expanding multi faceted business with his partner Wylie. Furthermore he is ‘known’ only to have designed their three showpiece businesses premises in prime locations. Quite. Even if he had local structural engineer like Robert McConnell assisting I struggle with that narrative. Yes he might have meticulously specified floor layouts, cabinetry, expensive plate glass and how he wanted the building to function but given his obvious prowess as a retailer, I suspect he was not short on self promotion either. Is it coincidental that:

i. An architect school had been located in the vicinity.

ii. This site might have had special resonance with John Baird I given its proximity to where he served his formative years. He is also known to have pioneered innovative cast iron design at Argyle Arcade 1827 & Gardner’s Warehouse Jamaica St 1856. Placing Wylie & Lochhead’s build of 1844/6 well within a window of opportunity.

iii. The decision by Greek Thomson to promote iron/steel framework externally in the beautiful Buckshead building almost directly opposite is curious. Structural concerns of the time aside, was Thomson paying homage to an old mentor by showing Baird, who was an early pioneer of cast iron structures, how far he’d come?

In 1853 after 20 years in existence Haldane’s Academy merged with the Government School of Design to become known under the rather clumsy moniker, School of Art of Glasgow and Haldane Academy. In 1869 this joint venture would move to a new location in the McLellan Galleries on Sauchiehall Street supported by Archibald McLellan who was a champion of the arts. (but possibly not the artists if his treatment of Stevenson, architect is true. A ‘fine’ architect, he allegedly ruined him and he never built again.)

Glasgow Style

By 1885, under the direction of Francis Newbery, a larger premises was needed for the art school. In 1896 one of Glasgow’s most significant architectural competitions was instigated. The local architectural firm of Honeyman and Keppie, presented a design by one of their junior staff. That architect was Charles Rennie Mackintosh (1868-1928). His design would cement a reputation and go some way to providing modern Glasgow with a new(er) identity. Glasgow could already claim to have had a strong visual identity, it was nothing new. Prior to this there had been:

1600s

Loggia: Situated around the cross. c1652. Inspired by the continent and possibly Inigo Jones’s Covent Garden of c1631. The idea was later leveraged again for a sheltered urban realm around Glasgow’s first West End at Wilson Street b1791.

Stone Built: After the two devastating fires of 1652 & 1677 Glasgow City decreed that houses should no longer be constructed of timber, using stone and brick and slate instead of thatched roofs. Over time the decree was beneficial to the look and feel of the city that was remarked on by many, not just Defoe. ‘Stately & well built’ would have projected confidence and some semblance of security and confidence from the ravages of fire. That alone would have been attractive to business setting up in the area knowing that their produce & stock was safer in Glasgow than elsewhere. Layer on top of that the burgeoning commercial success and wealth that was accruing from fishing and overseas trade resulted in ostentatious displays of wealth in the city streets such as the Palladian Shawfield Mansion of c1711.

1700s

Scalloped doorways: Reputedly found mainly on eastern seaboard of USA. Surviving examples can be found at John Craig’s 42 Miller Street (c1775) and William Hamilton’s 52 Charlotte Street c1779.

Arched Gateways: On gable ends.

Tripartite Window: In its original form known as ‘venetian’ in the western world. In its later form with sash opening known as a ‘Chicago’ window. But one could make a case for the ‘Glasgow’ window given how it proliferated amongst the early tenement designs from c1790s as they moved westward away from the mainly Scots baronial and Dutch styles.

The Grid: A pragmatic & efficient system.

As the 19th Century progressed Glasgow would evolve with the neo-classicism of David Hamilton and others, later the Beau Arts of late Victorian would flourish. It is this later period that now stamps its visual presence on Glasgow.

In 2009 The Glasgow School of Art was awarded the accolade of being the best building from RIBA’s 175 year existence. It was a building of great humanity, complexity and interest; built with love. It embodied the three principles of how we as humans respond to our built environment:

i. Coherence: ‘fitness for purpose’ – acutely attuned to its use.

ii. Fascination: embody a sensory richness/complexity that stimulates the psyche.

iii. Humanity: an ability to inhabit comfortably, easy to navigate & live with.

Making buildings that have humanity, complexity & interest that stand the test of time is no easy task. It takes skill. It takes a team, Macintosh was part of a team. Little is said in the city about Honeyman & Keppie leveraging and pushing the boundaries of technical innovation of the day that architectural historian George Cairn suggests it as being a contender for the crown of the first modern building in the west with air conditioning & heating system built in to the design c1890. One major advantage was that it allowed temperature in the life room to be independently controlled and so could be warmer than the rest of the building when needed. Cairn’s contends that it was the legacy of this innovative heating/cooling system, abandoned in the 1920s and to an extent forgotten until his 90’s thesis, that contributed to the recent fires being so devastating.

In Glasgow at the turn of the 19th century we had ubiquitous architecture of such a high standard, executed with the latest innovations in design, technology, engineering and construction that as others have noted hampered any real critique of what preceded.

A few names seldom get any recognition when discussing Glasgow’s earlier (Georgian) architecture that provided a foundation that others would later leverage to such great effect:

- Sir John Soane (1753-1837) A pioneer of Greek revival in the UK who I have already written about in the context of the Dennistouns of Colgrain and a possible early influence (unsubstantiated) on a certain David Hamilton.

- William Hamilton (c1730-c1795)

- Robert Scott (c1770-1839)

© Cicerone: MerchantCityGlasgow. All Rights Reserved 2023